Diane R. asked this question via our latest website survey, and it’s a good one. With all the hype about prevention, it makes sense for us to back it up! First, however, I’d like to cover what prevention is and put it into context.

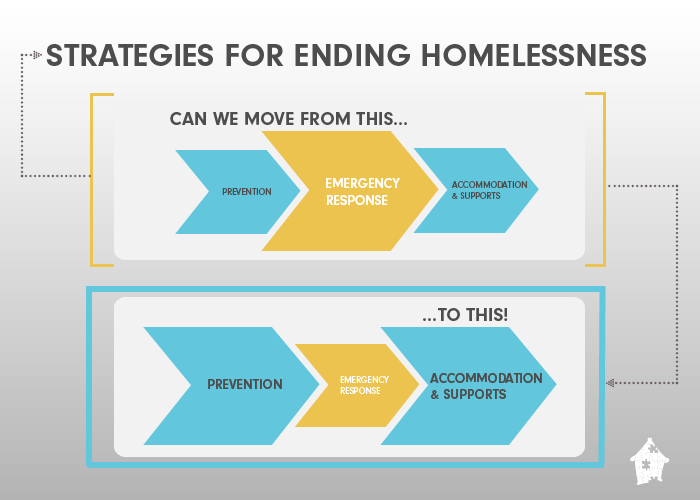

It’s no secret that in Canada and many other places in the world, our response to homelessness consists mostly of emergency services – shelters, makeshift drop-in centres, etc. While emergency services will always be necessary because, well, things happen, they are not a strategic solution. If homelessness were a disease, emergency services would be akin to a symptom-treating medication – important yes, but it doesn’t really cure the disease; it just manages it. In the words of the authors of the State of Homelessness in Canada 2014 report: “For years we have been investing in a response to homelessness that, while meeting the immediate needs of people in crisis, has arguably had no impact in reducing the scale and scope of the problem.”

A prevention-based approach to homelessness simply aims to keep people from becoming homeless in the first place. The question becomes not “how can we help people experiencing homelessness” but “what can we do to keep people housed?”

Kinds of prevention

Primary prevention – works to mitigate risks and usually targets entire communities, and can include information campaigns; education programs; anti- violence, racism and poverty activism; and early childhood supports.

Secondary prevention – identifies and addresses problems in their early stages. In homelessness, this would include efforts to help people keep their housing or find new housing quickly, including initiatives like rent banks, emergency assistance with utility and other bills, landlord-tenant mediation, and family mediation (includes many services that aim to avoid eviction, which agencies have reported as being successful).

Tertiary prevention – aims to slow the progression of a problem and/or reduce its likelihood of recurring. Regarding homelessness, this kind of initiative focuses on achieving housing stability. When implemented well, Housing First is an example of tertiary prevention.

This section was drawn from our prevention solutions page.

But does homelessness prevention work?

In a 2006 report, Burt, Pearson and Montgomery wrote: “Researchers (Lindblom 1997, Shinn, Baumohl, and Hopper, 2001) have concluded that strong evidence is still lacking that homelessness prevention efforts are effective, but the bulk of their criticism has to do with targeting and inefficiency, not with the underlying effectiveness of different activities.” The authors outlined four main areas for successful prevention strategies:

- ability to target well (includes sharing information across agencies)

- community is motivated to create change

- resources are maximized (private and public collaboration)

- has direction, sustainability, control and feedback

There is a growing body of research that supports Housing First, which aims to include all the aforementioned elements. Of the 1,000 participants in the At Home/Chez Soi study, 80% of people who received Housing First services remained housed after the first year. Additionally:

For many, use of health services declined as health improved. Involvement with the law declined as well. An important focus of the recovery orientation of Housing First is social and community engagement; many people were helped to make new linkages and to develop a stronger sense of self.

In Housing First in Canada: Supporting Communities to End Homelessness, the authors discuss eight case studies of Housing First programs across Canada, concluding the intervention is scalable and successful. But, as the authors note, it will take much more than change within the homelessness sector to truly address homelessness:

At the end of the day, the scalability of Housing First may depend on there being an adequate supply of affordable, safe housing, or on there being robust programs of rent supplements to enable housing people in market housing. Rent supplements address the issue of affordability within a tight rental market without necessitating the development and construction of new housing. Even in communities like Hamilton, which doesn’t have as tight of a market, the use of rental supplements has been necessary to make Housing First work.

No one strategy, program or solution type will ever end homelessness without simply increasing the availability of affordable housing. As Gaetz, Gulliver-Garcia and Richter (2014) wrote in The State of Homelessness in Canada, we need national, and cross-sector support in not just ending homelessness, but preventing it in the first place.

This post is part of our Friday "Ask the Hub" blog series. Have a homeless-related question you want answered? E-mail us at thehub@edu.yorku.ca and we will provide a research-based answer.