The desire to address inequalities and exclusionary practices within homelessness policy led Wales to become the first country to attempt to fully reorient homelessness services toward prevention and to make preventive services universally available. At the heart of the Welsh approach is a legal duty that requires municipal authorities to offer assistance to anyone who is at risk of homelessness or who has become homeless. If they are seeking help, there is a duty to remedy the situation within 60 days. This is a radical shift in how we deal with homelessness. In North America, prevention has not been a priority. A key question is whether and how such a prevention-based policy and practice can be adapted to the Canadian context and, in particular, how can it contribute to our policy and practice toolbox for preventing youth homelessness. To help us answer this question, Making the Shift Youth Homelessness Social Innovation Lab, co-led by the Canadian Observatory on Homelessness (COH) and A Way Home Canada (AWHC), partnered with Bridgeable, a Toronto-based service design consultancy. Over the past four months, the project team used a human-centred, design-based approach to prototype and test service elements of the Welsh Duty to Assist model and make strategic policy recommendations to improve the effectiveness of the policy moving forward.

Here, we share a summary of what we learned through the process and discuss next steps. For a deeper dive into our process and learnings, read the full project report, Guiding Youth Home.

Duty to Assist represents a transformative approach to homelessness. It moves resources from emergency responses upstream to prevention, allowing a whole new paradigm of care to emerge. Though the evidence proves that prevention is both cost-effective and leads to better outcomes, it’s still hard to imagine a world without the current volume of people on the streets, visiting emergency shelters and food kitchens. What does a new rights-based approach to housing look like, and how can we best prepare to adopt these evidence-based policies in practice?

With a focus on youth from the outset of this project, we looked to test out three hypotheses on the value to this policy of deploying service design:

- Taking the written policy recommendations of Duty to Assist and translating them into specific service interventions would provide the people delivering and managing homelessness services with greater clarity and, in turn, encourage higher rates of adoption.

- Using a co-creative approach that includes a broad section of system stakeholders (service agencies, youth who have experienced homelessness, Indigenous communities, funders, school boards, etc.) would help transform system actors’ mental models and the ways they relate to one another.

- Simulating a world in which Duty to Assist is already implemented would lead to direct insights into the logic of the policy.

We decided to focus the work on youth who are at risk of or who experience homelessness because of their vulnerability to a number of related hazards, such as declining health and mental health, trauma, addictions, and trafficking, at a time when they are in the throes of adolescent development. We also know that a large percentage of homeless youth (40%) have their first experience of homelessness before they even turn 16, and, sadly, the homelessness sector is not structured to offer any support at this age.

We considered, from the perspective of young people themselves, potential points of intervention. In other words, where are the institutional points of contact that could be mobilized to offer young people support? Where would the duty to assist reside? This led us to consider the potential role of schools (teachers and counsellors), child protection services, and other services where young people may be reachable. Because every young person who becomes homeless was in school once, school seemed an ideal place to begin our consideration of where intervention could occur.

Below, I’ll attempt to unpack each of these elements with explicit examples of how we applied Service Design and what we’ve learned so far.

- Taking the written policy recommendations of Duty to Assist and translating them into specific service interventions would provide the people delivering and managing homelessness services with greater clarity and therefore encourage higher rates of adoption.

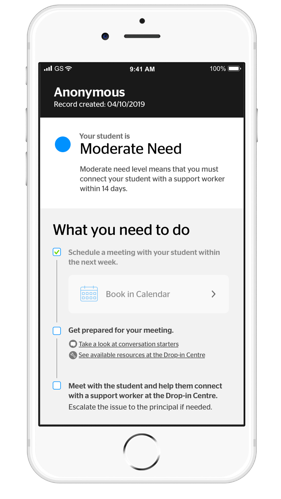

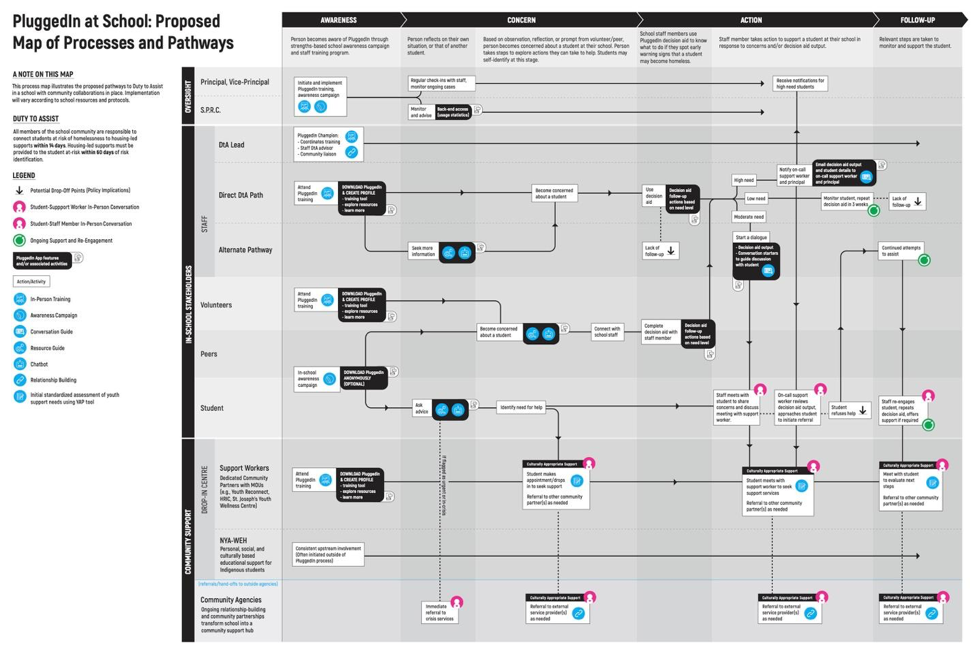

Our design work involved co-creation with the frontline staff who would be responsible for delivering new services. We worked with teachers and school board administrators on creating a tool that helps teachers to identify youth who could potentially become homeless. By working directly with staff on the front lines, we were able to iterate our design to include important features that teachers valued, such as recommendations on how to best start a dialogue and additional resources to make them feel better supported in this challenging and pivotal moment. These features show teachers and other frontline staff a level of detail that speaks to their particular work context and professional needs.

Teacher decision-support engine includes helpful conversation starters, a feature recommended by co-design participants.

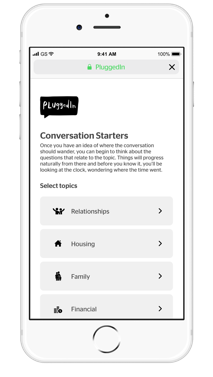

The design process also mapped and visualized how service elements fit into existing workflows, enabling frontline staff to see how their roles and responsibilities will change.

- Using a co-creative approach that includes a broad section of system stakeholders (service agencies, youth who have experienced homelessness, Indigenous communities, funders, school boards, etc.) would help transform system actors’ mental models and the ways they relate to one another.

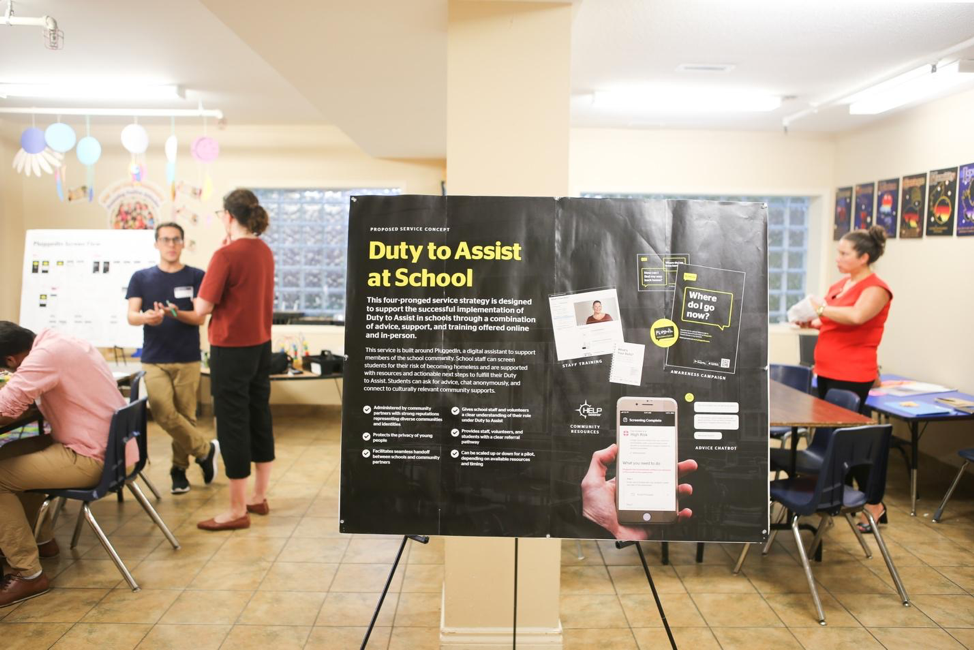

Co-design was run with an eye toward cross-functional collaboration. We deliberately placed different stakeholders who would not typically interact into co-design groups. In our sessions, we provided contexts to frame the work, such as home or school, and populated teams with individuals from areas such as the school board, social service agencies, and local Indigenous organizations, along with researchers and advocates. These actors created a new model of reference to transform their established roles and relationships—one that was aligned around the policy recommendations.

A diverse cross-section of system actors co-created new services for a future where Duty to Assist is an active policy, transforming their mental models and relationships.

We also ran sessions with youth who had experienced homelessness. They co-designed service elements, leading to a reframing of important dynamics around supports and services, such as addressing current power relations and social stigma.

Youth who have experienced homelessness attended a co-creation session at the Hamilton Regional Indian Centre to develop key elements of services, adding important context that increases the potential impact of the policy.

- Simulating a world in which Duty to Assist is already implemented would lead to direct insights into the logic of the policy.

By playing out the logic of the Duty to Assist recommendations as future services, we uncovered a number of strategic insights and possible unintended consequences. For example, in the process of identifying youth who have the potential to become homeless, there’s a chance that unconscious bias could lead to more Indigenous youth being reported to child protective services.

Additionally, Duty to Assist is a new regulation that is similar enough to the existing regulation Duty to Report that those working at the front lines may become confused about where one responsibility ends and the other begins.

We are pleased that many of our hypotheses in this experiment in policy and service design signal promising results. Moving forward, we hope to implement pilots to measure and evaluate the services while providing opportunities to iterate service concepts within the education system. Additionally, we will begin simulating change in other systems, such as the child welfare and criminal justice systems. All of this work will be used to inform and refine elements of the policy, with the ultimate goal of translating this evidence base and regulatory structure into impactful services that shift the paradigm from emergency response to prevention, leading to better outcomes for Canada’s citizens.

Our next goal is to run a full pilot of Duty to Assist in Hamilton. We hope that this will represent an opportunity to inspire a major paradigm shift in how we think about and respond to youth homelessness.