In our latest website survey, Terri G. asked us the following: “Have there been studies done linking mental health to addictions to homelessness as a trifecta of consequences (concurrent, rather than singular)?”

The answer is yes, there certainly has been. Much of the literature on homelessness discusses the prevalence of what most Western researchers and healthcare practitioners call “concurrent disorders” (or dual diagnosis, or orco-morbidity), defined by Health Canada as “a combination of mental/emotional/psychiatric problems with the abuse of alcohol and/or other psychoactive drugs.” There can be multiple mental health issues and different substances involved. In the words of CAMH’s “Beyond the Label” toolkit, “…the effects of one may compound the effects of the other, thus exacerbating symptoms and making the person’s life more challenging.”

While people with mental health issues don’t always have substance use problems and vice versa, both can make someone more likely to become homeless. As covered on our mental health page, “people with poor mental health are more susceptible to the three main factors that can lead to homelessness: poverty, disaffiliation and personal vulnerability.” Similarly, rates of substance abuse are high among people experiencing homelessness. There’s no concrete set of statistics and numbers vary by location, but rates of concurrent disorders are generally considered high. For example, the Toronto Street Health Report (2006) found that 26% of people experiencing homelessness would be considered as having concurrent disorders.

Beyond an individual focus

That said, both mental health and substance use are both individual/relational factors that, on their own, don’t automatically lead to homelessness. So even though they can certainly overlap and exacerbate each other’s effects, framing homelessness, mental health issues and substance abuse as equal but interrelated “consequences” isn’t really accurate.

Causes of homelessness are difficult to determine, partially because homelessness itself has an enormous effect on people’s abilities to cope and be healthy, but also because there are simply so many other factors to consider. By focusing on things like mental/emotional health and substance use, we place a heavy emphasis on the individual/social factors and ignore the larger structural (ie. poverty and housing availability/affordability, as discussed in the State of Homelessness in Canada 2014 report) and systemic (ie. gaps in service) issues that can also result in homelessness. The BC Social Planning Committee highlighted the problematic nature of disjointed services in their 2006 report, which advocated for innovative approaches:

The literature reports that individuals with a concurrent disorder who are homeless have more issues that need to be addressed than others with a concurrent disorder who are not homeless. Once homeless, they are likely to remain homeless longer than other homeless people. Most clients are unable to navigate the separate system of mental health and substance abuse treatment. In Toronto, for example, it was found that most mental health facilities were unable or unwilling to work with people who have an addiction, while addiction treatment facilities were not equipped to deal with people with a serious mental illness (City of Toronto Mayor’s Homelessness Action Task Force 1999). Often they are excluded from services in one system because of the other disorder and are told to return when the other problem is under control (Dixon and Osher 1995; Drake et al. 2001;Drake et al. 1997; Rickards et al. 1999; Bebout et al. 1997) (p. 6)

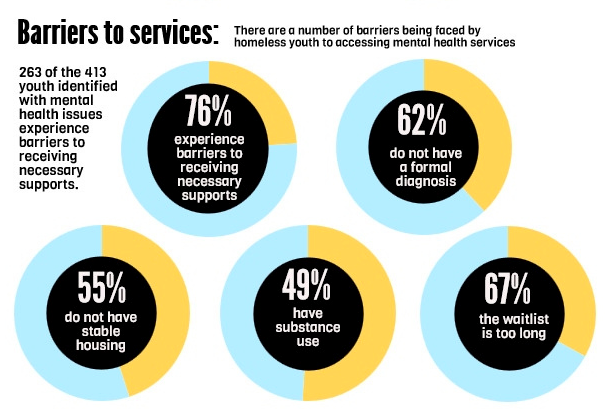

Though also in the individual/social realm, lack of support, trauma and victimization are often prominent in the lives of people with concurrent disorders. One Toronto study of street-involved youth found that a quarter of its participants had concurrent disorders. More of those participants “had experienced physical child maltreatment, greater transience, street victimization and previous arrest compared to youth without concurrent problems.” The same study estimated that youth with “concurrent problems” were nearly four times more likely to have been victimized in the past year. As shown in the infographic to the right, having both mental health and substance use issues can limit youth's access to certain services – some housing services will not be provided unless participants are deemed 'clean.'

In a Philadelphia study of 156 people experiencing homelessness who had been ‘dually diagnosed,’ researchers found that 89.6% had experienced at least once childhood risk factor. The most common included: living with parents who abused drugs, alcohol or both; out-of- home placements; parents with diagnoses of mental illness; and sexual abuse.

Best practices

People with concurrent disorders are often thought of as being particularly ‘hard to house.’ Even so, studies are increasingly showing support for the Housing First model – meaning, helping people experiencing homelessness secure housing before providing treatment or services for mental health or substance use issues.

Parhar et. al’s study (2014) compiled three Housing First case studies involving people with concurrent disorders in three Canadian cities: Vancouver, Edmonton and Regina. They found that supportive congregate housing is indeed effective, and recommended community involvement and client-specific design in creating supportive housing.

This post is part of our Friday "Ask the Hub" blog series. Have a homeless-related question you want answered? E-mail us at thehub@edu.yorku.ca and we will provide a research-based answer.

Photo credit: National Learning Community on Homelessness