How does homelessness impact the recidivism rates for youth involved with the justice system?

This question came from Marlene N. via our latest website survey.

As a 2006 Toronto report points out, most research suggests that the relationship between homelessness and incarceration is bidirectional: “That is, just as homeless people are at high risk of becoming incarcerated, prisoners are at high risk for becoming homeless.” Unfortunately, the criminal justice system in Canada is inextricably linked with homelessness.

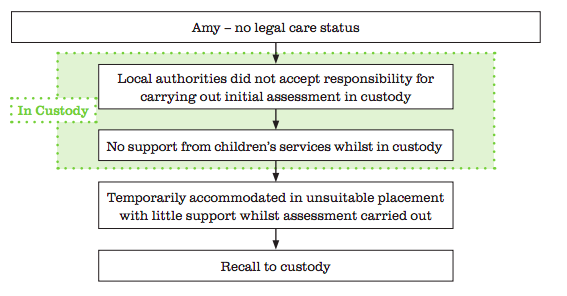

This is also true for youth involved with the criminal justice system, which is a highly vulnerable population. Specific data about youth offenders in Canada is difficult to obtain, but we know that many of these youth come from backgrounds of poverty, health issues, conflict and/or violence, and general instability. As a result, many do not have a stable, positive place to stay once they’ve been released; or families, friends and other social systems simply are not able to cope with caring for those who have been recently discharged. In the words of Jane Glover and Naomi Clewett (from their report, No Fixed Abode): “…periods of unsettlement in the transition periods just prior to release and immediately following release from custody can be triggers for disengagement from services, risky behaviour and re-offending.” The authors presented several case studies and outlined their paths to homelessness and back into custody (if that occurred). Below is one example of how they conceptualize the system failures that can lead youth back into custody.

In England, fewer youth are committing crimes but recidivism rates are very high at 74%. Glover and Clewett’s report highlights previous research from the English government that estimated youth recidivism rates could be reduced by 20% if stable housing was provided; and notes: “A Home Office evaluation concluded that 69 per cent of offenders with an accommodation need re-offended within two years, compared to 40 per cent who were in suitable accommodation.”

Similar rates have been found in a number of American studies. A 2013 study from the Washington state department found that 26% of youth released from juvenile detention facilities are homeless within 12 months of being released; and that recidivism rates were higher for these youth than those who had stable housing. Furthermore, the youth who experienced homelessness were found to have “a high rate of substance abuse, serious mental illness, rates of chronic illness, and higher mortality rate than youth released with no identified housing need.”

Potential solutions

A lack of stable housing and effective discharge planning also affects adult offenders, as research by Gaetz and O’Grady explores. Studies have also been done on the complex relationship between homelessness, trauma, poverty, and mental health—all of which makes people more likely to be incarcerated.

Other research supports solutions that go beyond limiting recidivism and improving people’s lives. A study about the cycle of homelessness and incarceration among Aboriginal women in Canada—among the participants, 56% reported a lack of housing contributed to recommitting crimes—concluded that “…there is a need for prevention and intervention supports for women living in poverty." The writers also argued that we "...need to address the systemic and institutional racism and sexism that continue to deny women the right to a living income, safe and affordable housing, and human dignity.”

As NextCity reported last July, taking a Housing First approach with people (and youth) leaving incarceration can dramatically reduce homelessness and recidivism amongst this population.

Glover and Clewett recommend that youth first be given the opportunity to stay with family whenever possible upon release, with additional support services to ease the transition. If this is not possible, the writers state that youth be provided with safe, supportive accommodation (with quality standards defined by the government) as they have seen success with this approach through their work at Barnardo’s. The writers also advocate for a cross-government strategy to support not only youth, but their families in order to move towards preventing homelessness.

This post is part of our Friday "Ask the Hub" blog series. Have a homeless-related question you want answered? E-mail us at thehub@edu.yorku.ca and we will provide a research-based answer.