In response to our latest website survey, Christopher .M. asked: “What special considerations must be given to those who are homeless and who have had contact with the criminal justice system?”

Homelessness is a challenge for anyone experiencing it, but it can be exacerbated by involvement with the criminal justice system. Many people believe that people experiencing homelessness are "criminals" and therefore deserving of their situation, but this is simply not the case. Not everyone who is homeless is criminally involved, but unfortunately, as I wrote in a previous post about rates of recidivism (re-offending) among youth, “the criminal justice system in Canada is inextricably linked with homelessness.”

When working with people experiencing homelessness who are also involved in the criminal justice system, there are many things to consider. They may, among other issues:

- Have difficulty finding the supports they need to secure legal services and representation

- Need transportation and/or additional supports for meetings and court appearances

- Require support regarding their transition to or from incarceration

- Be unable to find employment

- Not qualify for social assistance or other benefits

Here are some other things to keep in mind:

It's a bidirectional relationship

Some people think that homelessness leads to incarceration, but research has shown that the relationship between homelessness and incarceration is actually bidirectional. As Gaetz and O’Grady wrote in their 2006 report: “…just as homeless people are at high risk of becoming incarcerated, prisoners are at high risk for becoming homeless.”

There are many reasons for this, and they go far beyond the simple concept of “committing a crime.” Many studies have been done on the relationships between homelessness, trauma, mental health, substance abuse and poverty – this one from 2014 is particularly in-depth – all of which increase a person’s likelihood of becoming involved with the criminal justice system.

The stresses of homelessness combined with lifelong struggles with poverty, trauma and/or mental health issues often leads people to engage in criminalized behaviour to survive and/or cope. Often, a lack of supports and/or housing is also a contributor to offending and re-offending. In a study of Aboriginal women in Canada experiencing homelessness, 56% of participants reported that a lack of housing contributed to recommitting crimes.

Homelessness itself is criminalized

Furthermore, the criminalization of homelessness remains our dominant societal response to the issue, which complicates the great many problems that people experiencing homelessness already have. This refers to the various laws and policies that punish people who live on the streets, like anti-panhandling, loitering and vagrancy legislation. Such laws are aimed at not ending homelessness, but making it less visible and punishing those who experience it.

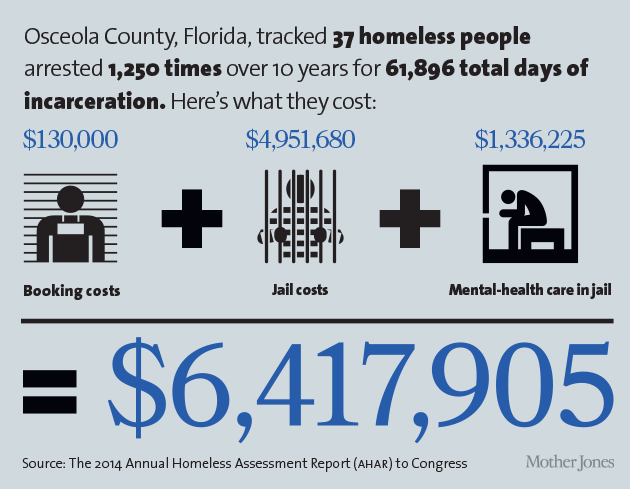

Last month, Vineeth shared a relevant infographic chronicling the immense cost of criminalizing homelessness – $6,417,905 in Florida, and pictured below.

There are similar consequences in Canada, where people experiencing homelessness are ticketed – being given fines that the state knows they cannot pay – for loitering, panhandling or "squeegeeing." In Ontario under the Safe Streets Act, 4 out of 5 tickets were given for non-aggressive acts according to a review.

It is much more expensive to target people experiencing homelessness than it is to house them, yet we continue doing it. A Housing First approach, rather than a punitive one, could greatly reduce homelessness among people who are criminally involved; and proper discharge planning can help people leaving incarceration avoid homelessness.

This post is part of our Friday "Ask the Hub" blog series. Have a homeless-related question you want answered? E-mail us at thehub@edu.yorku.ca and we will provide a research-based answer.