In this bi-weekly blog series, Abe Oudshoorn explores recent research on homelessness, and what it means for the provision of services to prevent or end homelessness. Follow the whole series!

With spring creeping in across Canada, the snow is melting away and people are returning to public spaces. With this re-exposure of land comes a frequent concern: litter. Earth Day in April is often used as a time when community members gather in public parks to remove litter that has accumulated through the winter and is visible after the snow melts but before the trees and bushes bud. However, these activities also bring citizens face-to-face with the reality of people living temporarily or long-term within parks and other public spaces in our communities. While some litter in parks is clearly just that, discarded garbage, other items represent encampments or stored personal goods of those without a home.

So what does this all mean to those who are living these experiences? How do they experience being property-less and inhabiting public spaces? Do they understand that their goods and temporary abodes are often deemed to be litter?

Jeff Rose explored this and many other issues through his doctoral research with the Hillside residents outside of Salt Lake City, Utah. Based in an ethnographic methodology, Jeff spent 16 months with the residents, at times fully immersing himself and residing in an encampment in the region. Jeff provides a rich description of being property-less and seeking residence in public spaces. This particular piece of his research focuses on the experience of a coordinated clear-out of the campsites by the Salt Lake County Health Department, precipitated by a request from the neighbouring quarry who was going to be doing blasting on their site.

What struck me in Jeff’s work is the concept of “cleanliness” and how perceptions of public spaces being unclean blur boundaries between objects and people, so that the residents of Hillside become themselves seen as pollution: “In the local case, the Hillside residents create pollution and are pollution, by the fact of their very existence” (pg. 18). A recent news report on another clean-out of the site since publication of this research confirms the point, with resident’s belongings termed as “garbage”, volunteers recruited to “clean up the mess”, and implications made about human waste disposal. However, Jeff’s research clearly indicates this is an invented issue.

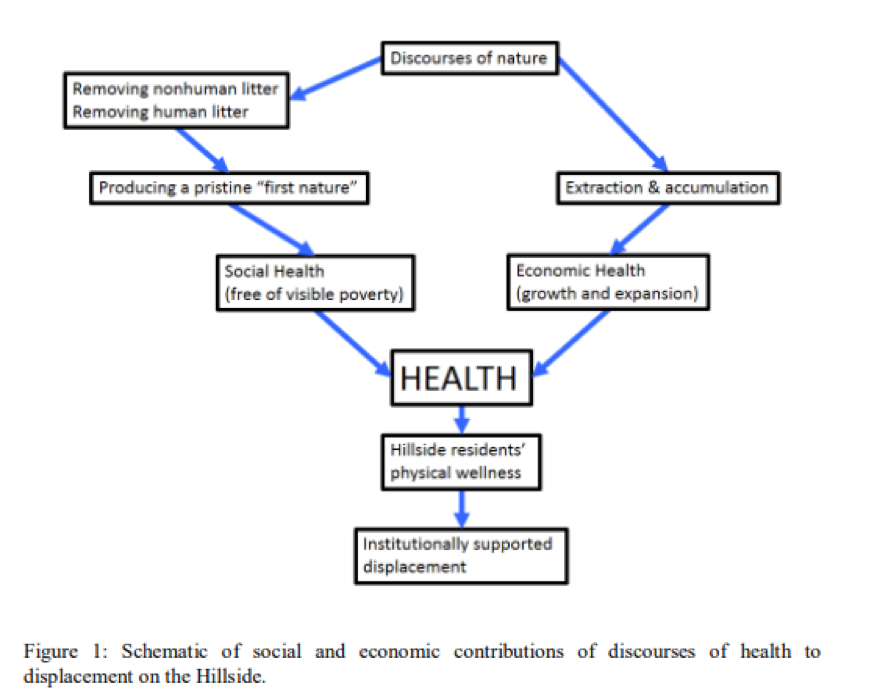

Jeff also links the local experience of being seen as an unclean element of public space with the broader structural issues of a society that has already pushed folks to (and beyond) the margins. “The Hillside residents did not feel they belong in the urban setting, but, through this pervasive and punitive logic of cleansing, they also did not seem to belong in the very nearby wildland environment, either; underlying exclusions was a logic of class relations” (pg. 18). Pushed out of private property, they are subsequently pushed out of public property. In Figure 1 he makes this links:

What does this mean for us as a sector? I think the first point is to start from a position of compassion when considering those who are living their existence in public spaces. This research illustrates the systemic nature of displacement and the limited options available to those living rough in finding dignity. Secondly, I would suggest that it calls us to consider the key purpose and questions of assertive engagement with those in urban encampments. This is not to say we shouldn’t reach out, but that the questions should be focused on the needs and dignity of the individual. What are their housing goals, and how can we assist them in achieving these goals in a manner that prioritizes their autonomy and choice? I would suggest that the actions of the Salt Lake County Health Department represent worst practice where there is zero consideration of the individual, zero focus on dignified engagement, and zero housing options provided.

Ultimately, Dr. Rose assists us in humanizing the experience of living in a public space and calls us back to asking the deeper philosophical questions about the structure of society and its consequences. Sometimes the only question that needs to be asked is, “Can I be of any assistance to you?”