Homelessness continues to be a visible problem in most Canadian cities. I would say most Canadians, when they think about how we respond to homelessness, would consider emergency shelters, drop-ins and soup kitchens – charitable programs set up to shelter and protect people while they are homeless – as central to our response.

But what about policing and law enforcement? What about the issuing of tickets and fines for panhandling or sleeping in parks? Such practices, which essentially criminalize homelessness, are every bit as central to our response.

At a time when the growing divide between rich and poor is in the spotlight, how we choose to deal with society’s most vulnerable – the people who occupy our streets not by choice but by necessity – is important to consider. The criminalization of homelessness runs counter to the “Canadian way.” It is out of line with our principles as a just and civilized society.

Two reports that highlight the downside of criminalizing homelessness in Canada have been  released this week. “Can I See Your ID? The Policing of Youth Homelessness in Toronto” (Bill O’Grady, Stephen Gaetz, Kristy Buccieri) and “La judiciarisation des personnes en situation d’itinérance à Québec : point de vue des acteurs socio-judiciaires et analyse du phénomène” (Dominique Bernier, Céline Bellot, Marie-Eve Sylvestre, Catherine Chesnay) both explore the impact of policing on homelessness. The first report, Can I See Your ID, reveals that despite strong evidence that panhandling and squeegeeing have declined over the past ten years, the amount of tickets issued under Ontario’s Safe Streets Act has increased exponentially, rising from 780 issued in 2000, to over 15,000 in 2010. All this has left homeless people with an accumulated debt of over $4 million dollars.

released this week. “Can I See Your ID? The Policing of Youth Homelessness in Toronto” (Bill O’Grady, Stephen Gaetz, Kristy Buccieri) and “La judiciarisation des personnes en situation d’itinérance à Québec : point de vue des acteurs socio-judiciaires et analyse du phénomène” (Dominique Bernier, Céline Bellot, Marie-Eve Sylvestre, Catherine Chesnay) both explore the impact of policing on homelessness. The first report, Can I See Your ID, reveals that despite strong evidence that panhandling and squeegeeing have declined over the past ten years, the amount of tickets issued under Ontario’s Safe Streets Act has increased exponentially, rising from 780 issued in 2000, to over 15,000 in 2010. All this has left homeless people with an accumulated debt of over $4 million dollars.

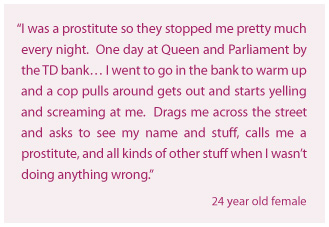

Interviews with street youth reveal that they receive a huge amount of attention from police, not only in the form of tickets, but also through regular ‘stop and searches’. This attention is not limited to those who are criminally involved – the evidence is clear, street youth are being subject to social profiling. In particular, being young, male and visibly homeless in downtown Toronto means you are very likely to have regular encounters with police. The second report also documents consistent practices of criminalizing homelessness across seven Canadian cities (Vancouver, Winnipeg, Toronto, Ottawa, Montreal, Quebec, and Halifax).

Interviews with street youth reveal that they receive a huge amount of attention from police, not only in the form of tickets, but also through regular ‘stop and searches’. This attention is not limited to those who are criminally involved – the evidence is clear, street youth are being subject to social profiling. In particular, being young, male and visibly homeless in downtown Toronto means you are very likely to have regular encounters with police. The second report also documents consistent practices of criminalizing homelessness across seven Canadian cities (Vancouver, Winnipeg, Toronto, Ottawa, Montreal, Quebec, and Halifax).

How does any of this make sense? Issuing fines to people with little or no money does not help them move forward with their lives. It alienates and traumatizes an already marginalized population and makes moving out of homelessness that much more difficult. Ample research from the United States highlights the negative impact of criminalizing homelessness (Culhane 2010; Ruddick, 1996; NLCHP, 2006; 2009). While we often consider the use of law enforcement – including both policing and incarceration – as a characteristically ‘American’ response to poverty, we need to accept and realize that we do the same thing in Canada (Hermer & Mosher, 2002; Sommers, 2005; Sylvestre, 2010). Whether this means creating new laws that target homeless persons, (banning panhandling or sleeping in parks), or simply using existing laws in a disproportionate or discriminatory manner, (tickets for drinking in public, jaywalking etc.), the goal is to harass people who are homeless so they stay away from public places – spaces that we are all entitled to use. The outcome of all this is debt, a greater likelihood of going to jail, and the outright violation of the rights of Canadian citizens.

In recent years, several Canadian studies have highlighted the bidirectional relationship between homelessness and prison (Gaetz & O’Grady, 2006, 2009; Novac, Hermer, Paradis and Kellen, 2007; Kellen et al., 2010). That is, being homeless means you are more likely to go to prison, and prisoners – unless they receive effective discharge planning and supports, are more likely to become homeless.

All of this raises important questions. If people are afraid of those who are homeless, should the police intervene? The answer is no. One might be afraid of someone because of the way they look, their second hand clothes, their ethnic background, or the colour of their skin, but that doesn’t mean they actually pose a real threat. Using police intervention to respond to public fear that is based on stereotypes and prejudice is unacceptable. Then why don’t we object when this happens to people who are homeless?

If the general public, business owners and politicians find homeless people annoying or unseemly and don’t want to see them on their streets or sidewalks, is there an obligation for the State to act? Perhaps there IS an obligation . . . but doesn’t it make more sense to address homelessness by ensuring there are the necessary resources and supports (including an adequate supply of affordable housing) to prevent homelessness in the first place or to help people move into permanent housing? Let’s stop treating the symptom through punishment, and instead let’s go for the cure!

To read the full reports, visit:

Can I See Your ID? The Policing of Youth Homelessness in Toronto