You ever see the Christmas cartoon, it’s Santa Claus and the Island of Broken Toys. I’m just a broken toy. Sometimes, who knows why, a million of units come out fine and one of them’s broken. And I think it’s just I’m broken somewhere. (Max)

For over a decade I’ve had the privilege of spending time with people who are homeless or precariously housed. In that time, and as part of a research project with adults experiencing homelessness in Ottawa, people have shared with me some of the struggles they face simply existing in their communities. Many stories share a common thread about ongoing and degrading forms of social exclusion and the toll it takes on people’s housing and well-being. It left me wondering about the subtle and not-so-subtle forms of exclusion people who are homeless encounter every day and to question how we can end homelessness if exclusion continues in many ways.

It’s not surprising that people who are homeless experience different kinds of exclusion. This exclusion has a profoundly negative impact on their sense of self, dignity, and health and well-being. People will often internalize this exclusion when they are repeatedly told, in words and in actions, that they are not welcome. This happens when people who are homeless lie down on the sidewalk, try to pass time in a coffee shop, or pitch a tent in the park. Some people will withdraw, avoiding public places like malls or busy streets in an effort to escape humiliation, violence, or ticketing.

I’m put in a different pile, you know that’s you guys over there and these rules and opportunities are there for you and everybody else is frolicking in the meadows and I’m stuck in the urban jungle just trying to survive on a day to day basis. (Daniel)

The Homelessness Industrial Complex

These feelings of exclusion pervade all aspects of people’s lives. Even homeless-serving organizations with compassionate and dedicated staff can inadvertently reinforce exclusion by focusing on individual causes and responses to homelessness.

One of the ways we can think about the response to homelessness is by situating it within the concept of the Homelessness Industrial Complex (I’m borrowing here from the non-profit industrial complex and the prison industrial complex). The Homelessness Industrial Complex, or HIC for short, points to the ways that the funding constraints, program models, and governmental mandates and strategies limit the kinds of change homeless-serving organizations can address, the programs they can offer, and the advocacy they can do. These restrictions make it very difficult to push for broader structural change, even when people working in the sector are keenly aware of the complex social issues affecting the people they serve. The HIC breeds competitiveness, territorialism, and siloing between organizations and inflexibility in how they are able to deliver their services.

Because of the nature of the HIC, our collective response to homelessness has largely focused on individual factors that seem ‘fixable,’ leaving little energy, funding, or capacity to imagine social transformation. With funding parameters, evaluation strategies, and much needed political and public buy-in to keep organizations going, it’s difficult to develop wide-scale plans to address the root causes of homelessness, like poverty, a lack of affordable housing, colonialism, discrimination, and gender-based violence. But it is possible to create programs targeting impulse control problems, dependency issues, and cognitive-behavioural patterns. Individual support is important, and we need a bigger emphasis on harm reduction and mental health supports for people experiencing homelessness. But things like mental health or addiction treatment shouldn’t be positioned as a panacea. Rather, they are complementary to structural change to truly prevent and end homelessness.

No matter where I am, I can’t blame the environment because that would be me being in denial. (Christine)

One of the problems with focusing almost exclusively on individual factors is that, again, people internalize these messages. A regular comment I get from some people in the sector and the public alike about this research is that people use mental illness or addiction as an excuse for how they became homeless. This couldn’t be further from the truth. Overwhelmingly, my research found that people blamed only themselves for their circumstances. Despite childhood trauma, victimization, intergenerational poverty, discrimination, family breakdown, or chronic health conditions, people who are homeless felt unable to acknowledge structural drivers of homelessness. In many cases they shouldered the weight of social inequity alone.

Ending homelessness includes inclusion!

If we’re going to prevent and end homelessness in Canada, we have to make space to think about the effect that social exclusion has on people who are homeless. We also must recognize how people experience exclusion differently and address these unique conditions. Even once housed, many people continue to experience social exclusion, isolation, and degradation. With huge challenges accessing housing and supports, social inclusion can be an afterthought, but it has an enormous impact on people’s well-being and ability to permanently exit from homelessness. If we want housing to stick, we need to include social inclusion.

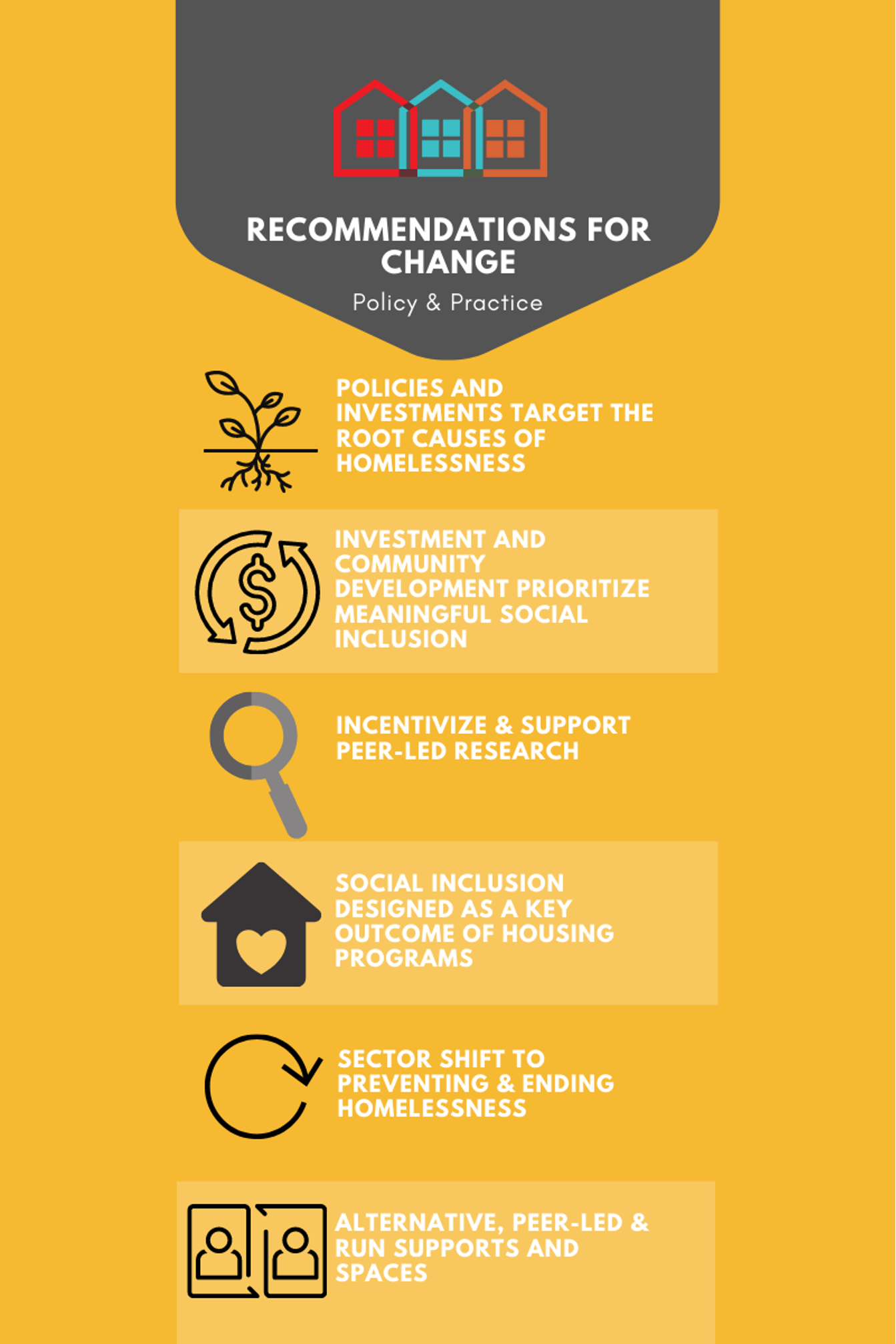

The good news is, we have growing evidence on what to do and lived experts who are ready to lead the way. There are research and program models aimed at fostering social inclusion. This can’t be the work of the homelessness sector alone, especially given the limitations put on the sector by the HIC. It requires a collective effort from multiple sectors and society at large. But the homelessness sector can provide the language, tools, and the path forward for developing social inclusion.

To learn more about homelessness and social exclusion, see A Complex Exile: Homelessness and Social Exclusion in Canada, available through UBC Press.

The analysis and interpretations contained in this blog post are those of the individual contributors and do not necessarily represent the views of the Canadian Observatory on Homelessness.