Australia discovered 'youth homelessness' earlier than other countries. Following a Senate report on Homeless Youth (1982), a national supported accommodation response to homelessness was developed. The Human Rights and Equal Opportunity Commission (HREOC) issued a historic report, Our Homeless Children, in 1989. Researchers in the mid-1990s raised questions about early intervention to prevent young people from becoming homeless in the first place as opposed to the prevailing focus on 'street kids'. This advocacy achieved some success when an incoming Liberal government convened a task force. A year later in 1997, Reconnect was launched, the first early intervention for youth homelessness program anywhere in the world, which still operates to this day.

Given this historical context, it might be thought that Australia has substantially rolled back youth homelessness; however, that is not the case. Despite receiving considerable public media attention and a lot of public policy discussion, the implementation of significant change has been limited. Why? Why has it been so difficult to open up the service system to early interventions?

Not an easy question to answer. Firstly, the typification of 'rough sleeping' dominates media stories and images of homelessness. Individuals sleeping in public spaces is how most people in the community think of homelessness in Australia, even though most individuals and families experiencing homelessness are in temporary shelter. Only 8,200 people per night slept rough in 2016, according to the Australian Bureau of Statistics. Secondly, after 35 years, the homelessness service system is still largely crisis-oriented. Talk to workers at the front-line who are usually under the pressure of unmeetable demands for assistance, ask them what needs to change, and they will most often say, "we need more crisis services and capacity". Based on their professional lived experience, their response is understandable, but it is not based on critical systems thinking. Thirdly, many homelessness agencies operating crisis services persist in advocating for more crisis services and mount cases for funding based on demand for services data. For their part, politicians have tended to respond by putting more resources into the crisis response. The problem of homelessness continues, and the number of people seeking help from the SHS system incrementally increases year by year.

The recent Inquiry into homelessness in Victoria was conducted by the Victorian Legislative Council Legal and Social Issues Committee. Australian parliaments produce a stream of committee reports which usually pass unnoticed. Only occasionally does such a report deserve to be described as 'a landmark report', that if implemented, would produce significant reform.

The Inquiry worked through 2020 under the difficult conditions of the COVID-19 Pandemic, receiving more than 450 submissions and holding eighteen hearings both in-person and online in Melbourne and regional Victoria. In the context of the recovery from the economic and social impacts of COVID, the multi-partisan committee issued a reminder to the Victorian Government and community that 'homelessness is one of the most complex and distressing expressions of disadvantage and social exclusion in our society and requires immediate attention by government'; that 'Victoria's homelessness system is overwhelmed with those in need, making it increasingly difficult for service providers to adequately respond to the complex and varying problems'; and that homelessness 'can have a lasting and traumatic effect' with huge long-term costs to the community when issues are not addressed earlier.

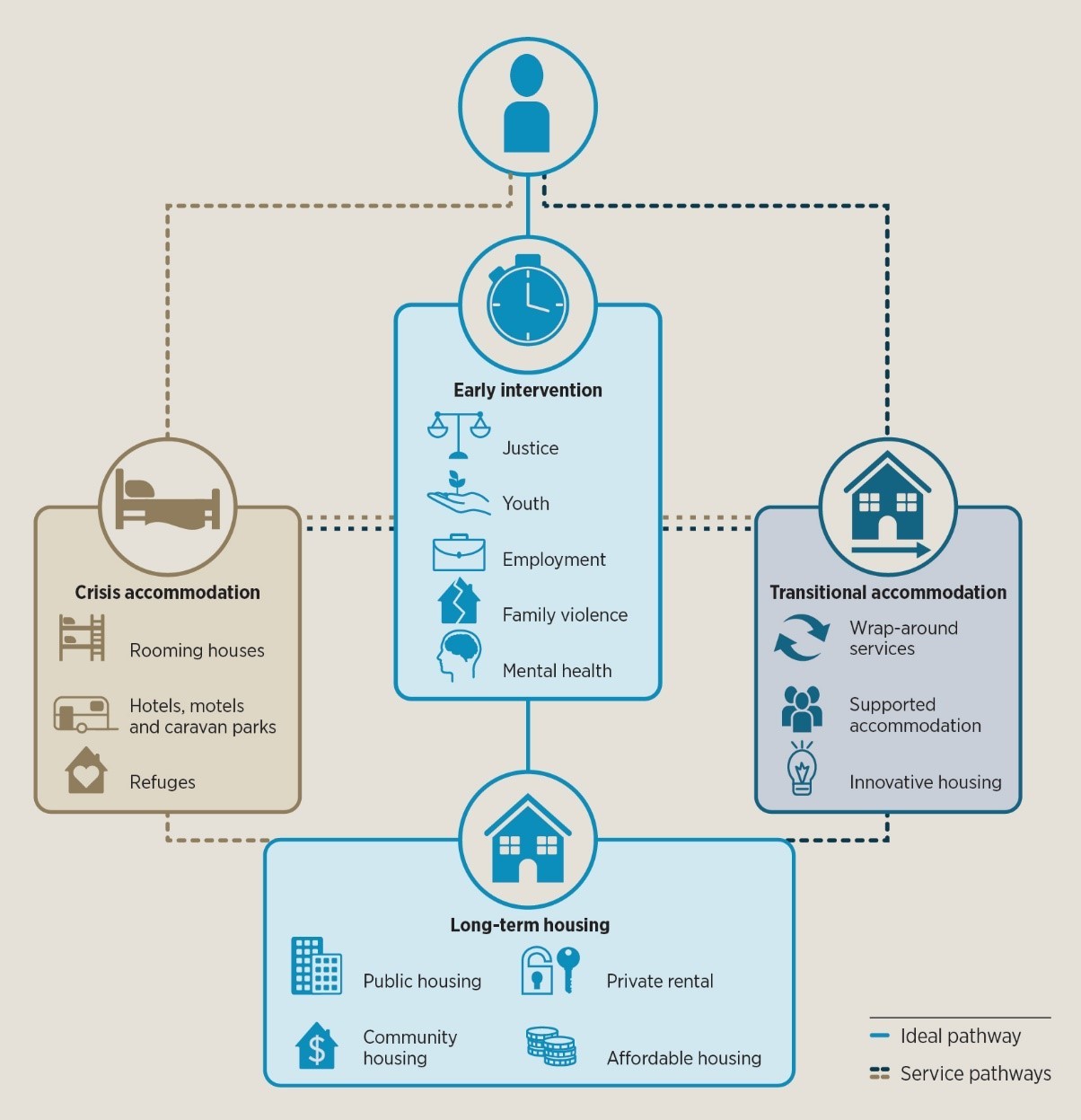

Notably, the Inquiry understood that a 'lack of long-term accommodation and early intervention programs in Victoria has led to an increasingly crisis-oriented sector'. The Inquiry examined the existing homelessness system critically, arguing that 'a more adaptable and flexible system is needed' in order 'to reorient away from a crisis response system' and move to 'a whole of government approach'. Early intervention was strongly advocated for: 'Early intervention involves the homelessness sector and other related sectors intervening as early as possible to prevent people becoming homelessness', 'early intervention is particularly critical for those who first experience homelessness at a young age. Prevention of homelessness amongst young people or intervening early is important to ensure that experiences of homelessness and disadvantage at a young age do not affect the life chances of an individual and increase the likelihood of ongoing homelessness into adulthood'.

The 'community of schools and services' model of early intervention (The COSS Model), pioneered in Geelong, was examined in detail (p158-166 of the main report). The Committee concluded that the COSS Model expanded to other parts of the state would have 'substantial benefits, including reducing the incidence of youth homelessness and providing overall cost savings' and recommended 'that the Victorian Government provide funding and support for the expansion of initiatives linked to the Community of Schools and Services model, with a minimum expansion to seven pilot sites that will include four metropolitan sites and three regional sites'. Qualified support was offered for more youth foyers in Victoria and additional funding for the innovative accommodation model developed by Kids Under Cover.

There is a major discussion of social and affordable housing as 'a crucial part of any solution … (and) … also a preventative measure'. The allocation late in 2020 of $5.3b over four years for social housing in Victoria is a major investment designed to pump prime the Victorian economy as the State recovers from COVID. However, Victoria lags other Australian states in the average annual investment in social housing, so the increase in social housing over the next few years climbs from a low baseline. Apart from the challenge of achieving long-term housing reform in Australia, a major advocacy effort is underway to rethink social housing for young people.

The Inquiry paid attention to emerging research about applying critical systems thinking to the problem of homelessness and what needs to change. The statement that 'In the Committee's view, Victoria's homelessness strategy must be reoriented away from crisis management to focus on a dual approach: (a) The promotion of early intervention programs; and (b)The procurement of sufficient long-term housing' (See Inquiry Summary Report) reflects a fresh more explicit reframing of policy thinking on homelessness in Australia.

Also, there has been a movement for change slowly but surely gathering momentum and seeking a shift from the current status quo to a place-based collective impact approach to addressing youth homelessness and other related adverse issues experienced by young people. The development of the COSS Model followed the work of the independent National Youth Commission Inquiry into Youth Homelessness (2008). An emerging idea in 2008, the COSS Model had become a well-developed model of community-based early intervention by 2016, attracting interest in other Australian jurisdictions and elsewhere.

When Inquiry Chair Fiona Patten stood in Parliament to table the Inquiry report, she said 'this is a report that this parliament will be proud of' and her message was refreshingly positive: 'we can solve homelessness … the simple cornerstones are preventing people from entering into homelessness and building more homes'. What next? - a National Youth Homelessness Conference in June 2021, a virtual event, has been organised around a Government-NGO sector cooperative project to develop a National Strategy to End Youth Homelessness and as a way of mobilising collective action for change.

David MacKenzie is Director and Tammy Hand is Senior R&D Manager of the Upstream Australia backbone support platform – info@upstreamaustralia.org.au

The analysis and interpretations contained in this blog post are those of the individual contributors and do not necessarily represent the views of the Canadian Observatory on Homelessness.