Young people who are involved with the child welfare system are on a timer. When a young person ‘ages out’ of care they lose access to many of the supports available through the child welfare system. While that age varies between provinces and territories, aging out usually occurs between the ages of 18-21. Once a young person reaches that age, they are expected to live as independent adults, with some supports available to them in some cases. For example in Ontario, a youth may receive some transitional assistance, such as an allowance of $850.00 per month up until the age of 21, and some youth may qualify for tuition support programs for post-secondary school.

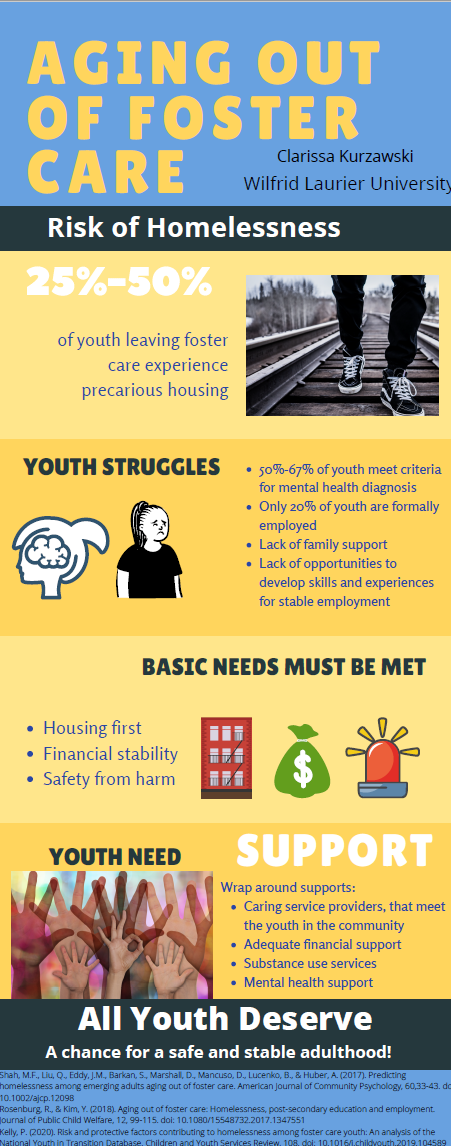

Although this transitional support is important, young people aging out of care do not have access to full wrap-around support, and some youth do not qualify for the extra financial support. As a result, youth are at risk of experiencing homelessness at least once in the year following their exit from foster care. Between 25%-50% of youth exiting foster care experience precarious housing, along with high rates of unemployment, lack of permanent connections with family, disrupted education, and struggles with mental health.

Leaving Foster Care

Youth in foster care often live in multiple private and group homes with many different caregivers. For example, in British Columbia a young person in foster care moves an average of seven to eight times over the course of their time in care. Switching foster care homes multiple times results in the youth experiencing instability and it becomes nearly impossible for youth to set down roots. Some youth who have child welfare involvement get caught up in the criminal justice system, including staying in detention centres in their teenage years. These incidences are often due to the effects of trauma, which can lead to substance misuse and mental health challenges that bring them to the attention of law enforcement. Some youth exiting care rely on criminalized activity to survive, for example, sex work, and in turn a criminal record creates further difficulties in securing suitable housing.

Many youth leaving foster care do not have the same educational and employment opportunities as other youth, leading to an employment rate 20% less than their peers. This lack of formal employment contributes to the risk of homelessness. Without a stable source of income, some youth struggle with food security and long-term housing stability.

Another issue for youth leaving foster care is the lack of familial support. Many youth leaving foster care have strained connections with family and may struggle to build a strong support network. While many young people across Canada continue to rely on their parents for housing, financial, social, and emotional support well into their 20s, youth leaving care are expected to be completely independent at age 18. This means they may not have anyone to fall back on if they miss a bill payment, are temporarily out of work, or a large expense comes up. This leaves many young people at risk for unstable housing.

Mental Health and the Criminalization of Homelessness

The factors described above – struggling to set down roots, find stability, or supportive homes– point to the institutional and systematic barriers youth face as they age out of foster care. Aging out is a key vulnerability point for homelessness, especially for those youth who have faced significant disruption in their lives, such as unstable placements and frequent placement changes.

When youth exit care without a clear transition plan, some struggle to navigate the housing market, relationships with landlords and roommates, and finding formal avenues for accessing income. Youth exiting care are more likely than youth who haven’t been in care to live in risky situations such as: renting rooms and illegal housing; falling victim to landlord or lease holders’ whims, such as unlawful evictions; and potentially being exposed to victimization or other dangerous situations. Of particular concern for young women and gender-diverse youth exiting foster care is human trafficking. In a report out of the U.S., 75% of survivors of human trafficking had foster care involvement.

Young people who are homeless or are living precariously often find themselves being watched by police, socially profiled, and receiving tickets for minor offences. These practices disproportionately impact Black, Indigenous, and youth of colour. This kind of surveillance creates criminal records for youth who were in foster care who lack proper resources and systems support as they learn to live independently, leaving them at risk of being stuck in a cycle of homelessness and criminal justice involvement.

Towards a More Successful Outcome

Youth exiting foster care are overcoming many different adversities, through no fault of their own, and need a clear plan to start their adult life. Young people who have received comprehensive transitional planning have increased success in maintaining stable and adequate housing. Transition planning involves a hands-on approach from foster care staff and includes taking the time to assess the young person’s needs, help them secure housing and ensure they have adequate financial and social supports to stay adequately housed. All youth need guidance and support to start their adult lives. This means youth in care need a system that allows for kindness and understanding; not punitiveness or an extension of the criminal justice system. More resources need to be made available for transitional housing for youth aging out of foster care to provide them with a safe and stable living situation as they become more independent. With supportive transitional housing, youth are able to receive a hands-on approach to start their adult life on the right foot, and reduce their risk for homelessness.

The analysis and interpretations contained in this blog post are those of the individual contributors and do not necessarily represent the views of the Canadian Observatory on Homelessness.