In this bi-weekly blog series, Abe Oudshoorn explores recent research on homelessness, and what it means for the provision of services to prevent or end homelessness. Follow the whole series!

I have always struggled a bit with the statement, “Homelessness can happen to anyone.” I understand the value of using this to grasp people’s attention, as I suppose it decreases some of the us/them dichotomy that exists between the housed and the unhoused. If we see ourselves, our friends, and our families at risk of homelessness then perhaps we are more empathetic towards those who have experienced housing loss. On the other hand, I think this tells a bit of a false story.

Because, while homelessness can happen to anyone, it happens most to those experiencing poverty, Indigenous people, and other racialized people. Highlighting how homelessness can happen to anyone helps us understand that unanticipated crises are often at the root of housing loss, but it simultaneously hides the systemic elements of homelessness that are linked to poverty and related inequities.

Patrick Fowler, Peter Hovmand, Katherine Marcal, and Sanmay Das point this out, stating,

“Globally, marginalized communities disproportionately experience homelessness. Homelessness is much more common among the poor and minorities in terms of race/ethnicity, sexual orientation and identity, and institutionalization and among those with physical and mental disabilities compared with the general population.”

Why is this important? This means that solving homelessness involves much more than individualistic approaches to personal challenges, and instead points to a focus on policies, systems, and structures that can be transformed to prevent housing loss.

Fowler, Hovmand, Marcal, and Das (2019) explore exactly this in their study “Solving Homelessness from a Complex Systems Perspective: Insights for Prevention Responses”. They highlight how responding only at the individual or family level is a fraught process as the causes of homelessness, experiences of homelessness, and levels of need are incredibly diverse. Simultaneously, resources for support are limited and tools to prioritize this support show limited validity and reliability. Few countries track prevention services in the context of homelessness, and most are seeing increased focus of supports to those with highest needs at the expense of more preventative services. While lip-service is paid to prevention, in reality funding continues to shift to downstream responses.

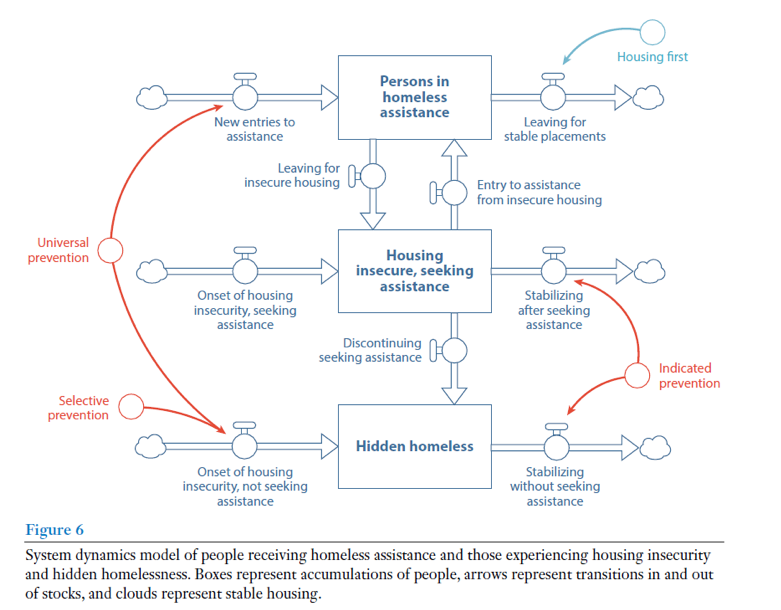

So, what if instead we could model the complex systems of homelessness in a way that accounts for both entries to and exits from homelessness? In doing so, the best points of intervention could be identified, as well as promising interventions. This is what Fowler and colleagues (2019) have constructed, a complex system computational model as follows:

Running simulations through this model they found the following:

- Optimizing housing first approaches results in incremental reductions in the number of persons in homeless assistance with no impact on the rates of housing insecurity;

- Prevention always outperforms housing first adaptations;

- Optimal response to homelessness comes from a multipronged approach that incorporates prevention with housing first.

So what does this all mean? Designing a homeless prevention system that shifts resources from prevention to support of those individuals with the highest need priority can have an unintended consequence of ultimately increasing service need. Therefore, while prioritization assessments can support service decisions for managing those already homeless, the greatest investment payoff will come from investing in preventions. While making a shift towards prevention can mean delayed results versus just focusing on rapid rehousing of those who are chronically homeless, the long-term outcomes are better. Therefore, coordinated access systems should also be designed to direct those to supports who are at risk for housing loss rather than only supporting those already homeless.