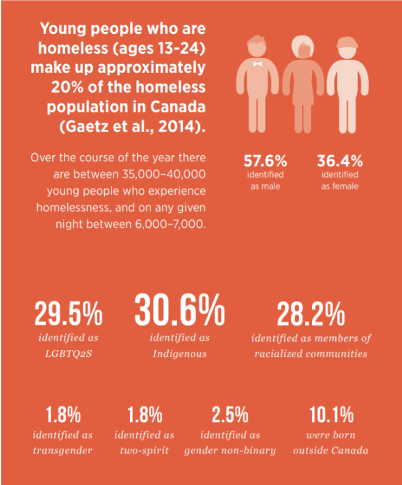

There are many personal and structural factors that create pathways into homelessness, including natural disasters, relationship breakdowns, unaffordable housing, job losses, and discrimination. Homophobia and transphobia in Canadian families, cities and institutions can lead some youth to find themselves living on the streets and trying to navigate the shelter system. In 2016, Without a Home: The National Youth Homelessness Survey found that 20% of all youth who are homeless identify as LGBTQ2S. This population is more likely to experience parental conflict and physical, sexual, or emotional abuse that contribute to their state of homelessness.

In 2013, the City of Toronto Street Needs Assessment included a question about gender identity and sexual orientation for the first time. Prior to that, it was extremely difficult to determine how many LGBTQ2S youth were experiencing homelessness in Toronto.

During that year, the assessment revealed that 20% of the youth in the shelter system identified as LGBTQ2S. However, the actual number of those experiencing homelessness in Toronto is estimated to be closer to 30% due to the hidden homeless population who do not access shelter support services.

What We Know

Alex Abramovich, a CAMH researcher, has done extensive work over the past decade examining LGBTQ2S youth experiences of homelessness. His study published in the book Youth Homelessness in Canada described the experiences of homeless queer and trans youth in Toronto. He found that many were attracted to Toronto as it was advertised as safe for LGBTQ2S people, so they left their communities in the hopes of finding support tailored to them in the big city. Instead, they found there were few specialized support services and no specialized shelters for LGBTQ2S street-involved youth. Many experienced some form of homophobic or transphobic violence in the city and sometimes in its shelter system.

The youth interviewed in Abramovich’s study explained how homophobic and transphobic violence in the shelter system comes in many forms, such as erasure, forced outing, and physical violence from other residents. These types of experiences were shared in a moving digital storytelling project created by a youth named Teal. Intake forms, administrative data and day to day operations did not include the experiences of LGBTQ2S youth, and many staff did not recognize this or have formal training around anti-homophobia or LGBTQ2S culture and terminology. Sleep spaces and bathrooms were often segregated by birth sex, and specific beds were allocated to transgender youth, forcing some to out themselves. When faced with physical violence from other residents, youth reported that there was often little response from the staff. Abramovich’s research strongly recommended creating specialized shelters for LGBTQ2S youth where they can feel safe and accepted.

The Specialized Shelter and Outcomes for Youth

This recommendation came to fruition in 2016, when the YMCA Sprott House first opened its doors. Sprott House is Canada’s first transitional housing program for LGBTQ2S youth, and the first specialized shelter for this population in Toronto. The program houses 25 LGBTQ2S youth between the ages of 16-24 and has been operating at capacity since opening. In a case study, the director of the Sprott House describes the ways that staff support youth by openly talking about gender and sexuality, local politics and policies that impact them, and by encouraging inclusive and considerate language such as asking for pronouns. They also address issues of racism that Black and Indigenous LGBTQ2S youth face and often debrief with them when they come home to Sprott House.

Last year, Abramovich published research about the experiences of the first cohort who lived in Sprott House. Each participant completed a survey and in depth-interview both when they first entered and then when they transitioned out of the program. Youth also shared their experiences prior to living in Sprott House, explained how living there impacted them, and made suggestions on what could be improved. Overall, youth described the program as one that provides them with safety, stability, connection, and community. The sense of safety helped them feel comfortable participating in group activities where they could socialize with others without fear of how they would be treated. This fostered a sense of belonging and acceptance that they never felt before in housing settings, which had a positive impact on their mental health.

Despite these improvements, many reported psychological distress on survey scales, indicating poor mental health before and during their stay. Included in this distress were high rates of self-harm, suicidality, and substance abuse. Very few reported slight improvements after their time at the Sprott House. Youth indicated a lack of direct mental health support and suggested a need for more on-site mental health workers to be present on a regular basis.

What Now?

More needs to be done to prevent and end LGBTQ2S youth homelessness in Ontario. The opening of YMCA Sprott House is a step forward. However, ongoing evaluation of this program is needed. Replicating this research with more cohorts and pursuing longitudinal research could provide a better examination of the short- and long-term impacts Sprott House has on its residents. This could also help make recommendations for future specialized programs that are needed for this population.

Sprott House is only one shelter program, and its limit of 25 youth per year falls short of the total amount of LGBTQ2S youth needing its services. Furthermore, as a one-year transitional housing program, it cannot adequately meet the needs of those with mental health issues. Creating other programs for this population that have a longer time frame, such as permanent supportive housing, may be a way to support youth who have mental health needs or require more time to achieve stability.

Finally, preventing LGBTQ2S youth homelessness is key, and the City of Toronto cannot tackle this alone. Currently, Alberta is the only province in Canada with a provincial strategy to prevent and end LGBTQ2S youth homelessness. Implementing such a strategy could lead to the creation of LGBTQ2S specific housing options, shelters, and programs. As Alex Abramovich says, the time to prioritize LGBTQ2S homelessness is now. The YMCA Sprott House was the first step, but we’ve still got a long way to go.