Prevention is the key to ending youth homelessness, but what do the people on the front lines think of it? And what do they know about the proven interventions designed to do this work? If they know about the interventions, are they interested in putting them into practice? What kind of support would they need to do it?

This past spring, the Canadian Observatory on Homelessness conducted a needs assessment targeting the youth homelessness sector to answer these questions. This resulted in 153 responses from across the country, which represents a strong response rate that should give confidence in the results. In a report recently published on the Homeless Hub, COH’s President and CEO, Stephen Gaetz, lays out the survey’s findings.

On the Need for Prevention

In the results, most striking is that the youth homelessness sector is very supportive of prevention. Almost 90% of respondents agreed with the statement, “Prevention is necessary to solve youth homelessness.” This was a welcome surprise, because it shows that efforts to educate the sector about the importance of prevention have been successful. It means that, in the future, awareness raising can focus on different aspects of the issue.

Being aware of the need for prevention is not enough though, which is why the survey went further and also gauged interest in five key interventions for preventing youth homelessness: Housing First for Youth (HF4Y), Family and Natural Supports, (FNS), Reconnect, Duty to Assist and Upstream.

Awareness of Prevention Interventions

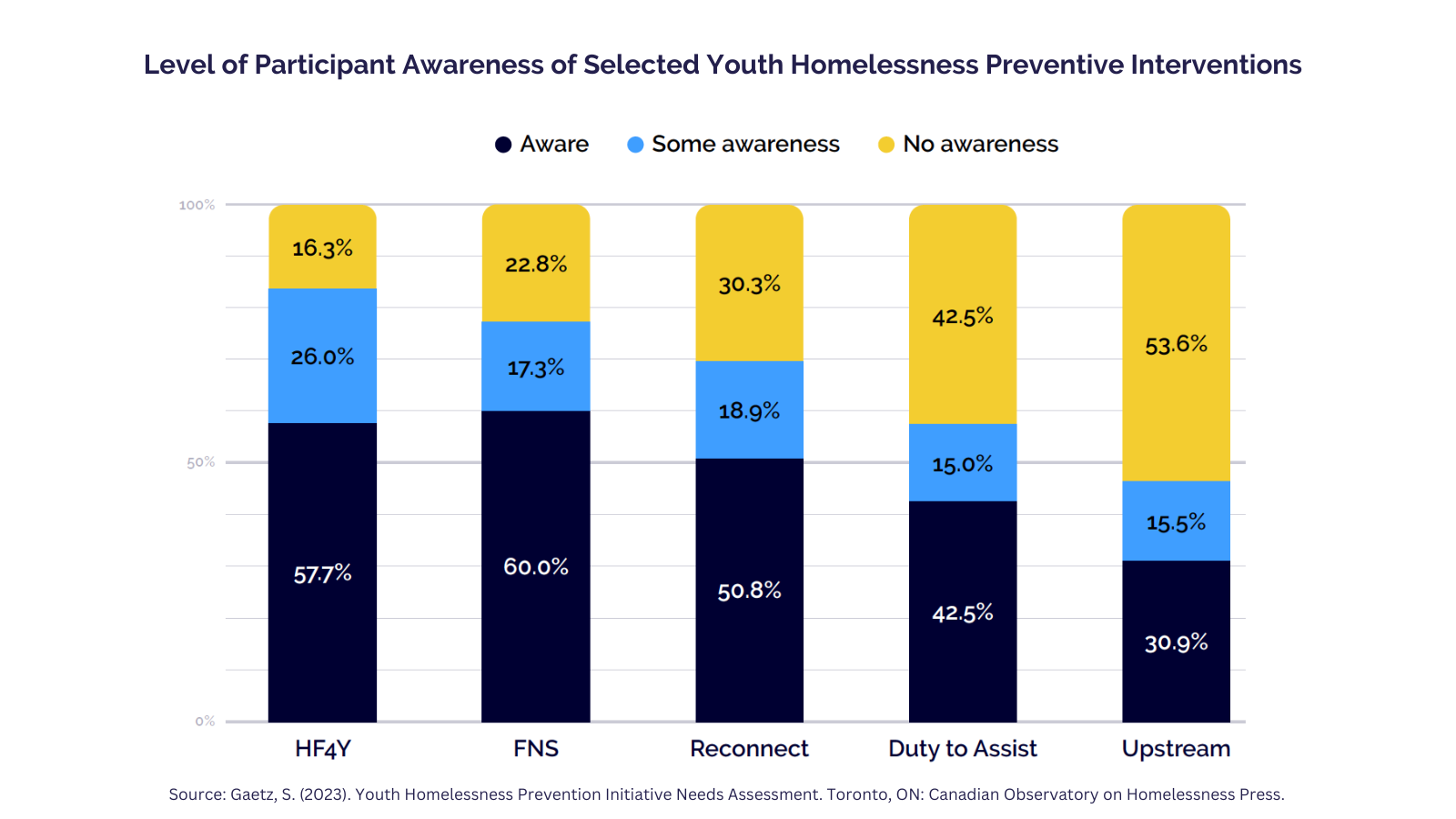

For the most part, the survey respondents demonstrated some level of awareness of the prevention interventions in question. The highest levels of awareness were for HF4Y and FNS, where 83.7% and 77.2% of respondents, respectively, had some awareness of the interventions. However, for Duty to Assist and Upstream, 42.5% and 53.6% of respondents, respectively, had not heard of the interventions.

The survey shows there is room for growth in terms of awareness of all five interventions. For each intervention, at least 65% of respondents noted that they would like to learn more. In particular, there was a very high level of interest (over 83%) in learning how to adapt HF4Y to meet the needs of Indigenous young people.

And what about the desire to put the interventions into practice?

Interest in Implementation

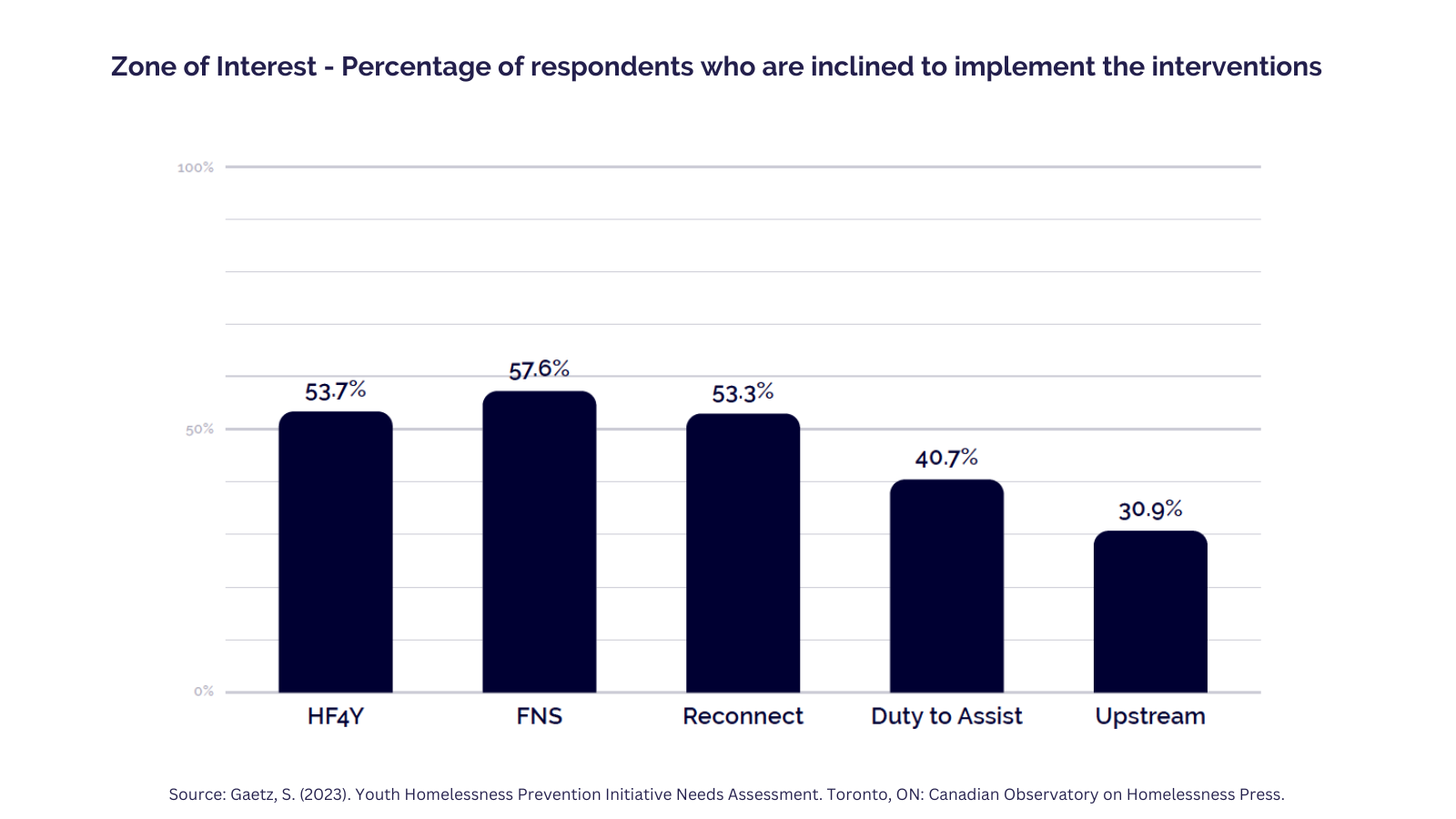

One goal of the survey was to identify the degree to which respondents had interest in implementing the interventions. Respondents were considered interested in an intervention if one of the following were true:

- They identified that the intervention would help their organization achieve its goals.

- They stated their interest in implementing the intervention (although they may currently lack capacity).

- They actively plan to implement the intervention (although they may need more support).

- They are currently running a pilot of the intervention.

- They have implemented the intervention as a core program.

A high percentage of respondents—62.7%—were interested in at least one of the five preventive interventions. The interventions respondents were most interested in were HF4Y and FNS, which were also the interventions about which respondents had the most knowledge. There was, however, significant levels of interest in all the interventions.

What can we do to convert that interest into action?

Capacity Building and Support

Although 90% of respondents understood that prevention is the key to ending youth homelessness, only a quarter felt their organization had the resources, knowledge and capacity to do prevention programming. This shows the shift to prevention will not happen without support. The research participants indicated the following needs:

- More information: Over 65% of respondents said they needed more intervention and training on the five interventions.

- More support from communities: Over 90% of respondents said their community needs to do more around youth homelessness prevention. This is consistent with what we often hear from members of the National Learning Community on Youth Homelessness: neither youth homelessness nor prevention seems to be a priority for their local Community Entity, which governs the local homelessness strategy.

- Dedicated funding: Over 80% of respondents said they need dedicated funds for preventive interventions. In the absence of new funding, there is a significant “opportunity cost” - community organizations are put in the unenviable position of having to stop funding some current activities to move in a new direction.

- Training and technical assistance: About 75% of respondents said that having access to quality training and technical assistance would be necessary for them to successfully implement the preventive interventions.

In total, 55.8% of respondents expressed interest in implementing at least one of the interventions, but identified they needed support. For any given intervention, between 35.8% and 46.2% expressed this view.

Innovation and transformation cannot occur without the right organizational capacity— many organizations want training but are unsure of where to get it. This shows that informing organizations of where they can access training and technical assistance could make a real difference in seeing preventive interventions put into practice.

Takeaways

Prevention is broadly recognized within the sector as being necessary for ending youth homelessness.

Many organizations have a good understanding of what prevention entails and know about the prevention interventions in this report, although providers still expressed a need for more information.

However, information alone is not enough. Perhaps the strongest message to come from the youth homelessness prevention needs assessment is the need for enhanced organizational capacity building. Providing targeted training and technical assistance is a key step for the future.

Finally, service providers felt that they needed much more support to get their communities on board with homelessness prevention. This corresponds with what we have learned from the National Learning Community on Youth Homelessness: many community entities do not prioritize youth homelessness or, in particular, prevention.

None of this will just happen organically. Higher orders of government need to support the work of capacity building and make investments in effective preventive interventions.

For more details about the findings of the youth homelessness prevention needs assessment, see the full version of the report here.

For more information about Housing First for Youth, Duty to Assist and Youth Reconnect, check out the free, self-paced trainings available on the Homelessness Learning Hub!