This question came from Celidh W. via our latest website survey: “With the extremely long waitlist for social housing, it seems almost impossible for individuals facing homelessness to gain access to affordable housing. What policies/procedures/changes could be implemented to help ensure more people can actually obtain housing when they need it most?”

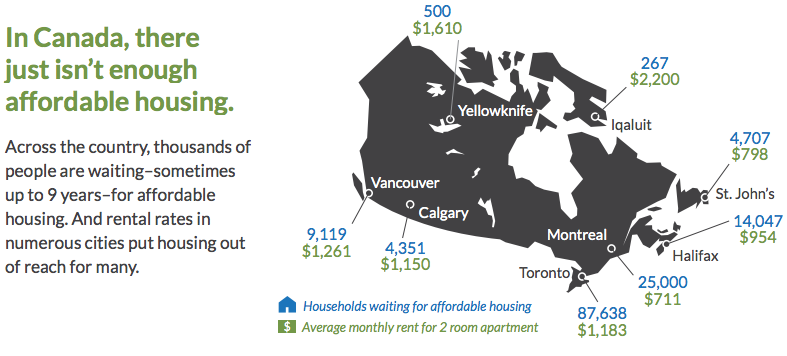

As Celidh pointed out, the waitlists for social housing in most Canadian cities are extraordinarily long, leaving many people waiting for years. As the following graphic illustrates, demand exceeds supply in almost every major urban area:

Waiting isn’t a luxury that many people experiencing homelessness have, so what can we do to make sure they can find affordable housing when they need it?

Engage the private market

One way to help rapidly re-house people is to form partnerships with other non-profit organizations, private landlords and/or property management companies. In tight rental markets, focusing on social housing alone will yield only more waitlists, so it’s crucial to add privately owned housing to the list of potential shelter for folks. (For more information, check out my post on ways some organizations have engaged with private landlords.)

Reduce barriers

Using a Housing First approach – which doesn’t place any restrictions about housing “readiness” – is a key component in reducing barriers faced by people who have mental health, substance or other issues. For example, many (although not all) people at risk of or currently experiencing homelessness use substances and are often asked to be abstinent before they can apply for housing. This is simply not a realistic goal for everyone, and most people who use substances are able to retain housing.

There are other more systematic barriers that many people face as well. A 2011 study of housing services in Edmonton found that documentation (such as photo ID) and eligibility restrictions (criminal records, age, etc.) present significant challenges to securing social housing for many people. Changing policies at this level to make it easier for people to access housing – or employing more people to help applicants with the process – could help reduce these barriers.

Connect with other services

On our website, we often write about the systems approach, which is a “strengths-based, culturally relevant, participatory framework for working with individuals with complex needs.” Most services related to homelessness are fragmented – existing in different areas with different mandates, and they don’t always work well together. People are left to navigate a sea of bureaucratic organizations that they may not understand. Streamlining services and making them easy to access – like offering onsite identification clinics, counselling, or help with social assistance applications – can make a big difference to someone looking for housing. Furthermore, connecting with organizations that do master leasing, help with damage/security deposits, or run Housing First programs could present more options for people in need.

Supporting preventative funding and measures

Rent supplements and other forms of financial assistance are often crucial to helping people avoid homelessness in the first place. Knowing how to help people access these funds and advocating for more of them can not only help people secure new housing, but it can prevent them from becoming homeless in the first place.

Social assistance rates are woefully behind costs of living and do not provide most people with enough money to pay rent and cover other basic expenses. Supporting changes proposed in poverty reduction strategies is an important part of ending homelessness altogether.

Advocating for more affordable housing

This is the most difficult to achieve, but also the most important in terms of looking at homelessness on a grand scale: we simply need more housing (emergency, transitional, supportive and permanent) that is decent, appropriate and affordable. The State of Homelessness in Canada 2014 report recommended that 88,000 new units be built over the next ten years.

In order to meet that number or one near it, all levels of government (as well as housing developers) must be held accountable for housing strategies and promises. Many of these declarations and budgets contain policies that can help increase the affordable housing stock. For example, Ontario has recently proposed inclusionary zoning, which would mandate that developments over a certain size include a certain percentage of affordable units. If we are committed to ending homelessness, we need to ensure that people have appropriate and affordable places to go.

Photo credit: Affordable Housing in Canada - Citizens for Public Justice