Our question this week comes from Tabitha Maria G. in our latest website survey: Why are women fleeing violence in traditional housing considered housed when in fact they're at imminent risk of homelessness?

How people are assessed (housed vs. not housed) depends on what definition of homelessness someone is working with. For example, some people think that only people living on streets or staying in shelters can be considered homeless. As Tabitha is pointing out, people in temporary, transitional or otherwise precarious housing situations can also be considered homeless.

Defining homelessness is often more complicated than people think. It wasn’t until the past few years that people in housing, education and social services agreed on a single definition of homelessness. The one we use here on The Homeless Hub was developed by folks at The Canadian Observatory on Homelessness and endorsed by community workers, researchers, policy analysts and government organizations. It describes homelessness as:

…a range of housing and shelter circumstances, with people being without any shelter at one end, and being insecurely housed at the other. That is, homelessness encompasses a range of physical living situations, organized here in a typology that includes 1) Unsheltered, or absolutely homeless and living on the streets or in places not intended for human habitation; 2) Emergency Sheltered, including those staying in overnight shelters for people who are homeless, as well as shelters for those impacted by family violence; 3) Provisionally Accommodated, referring to those whose accommodation is temporary or lacks security of tenure, and finally, 4) At Risk of Homelessness, referring to people who are not homeless, but whose current economic and/or housing situation is precarious or does not meet public health and safety standards. It should be noted that for many people homelessness is not a static state but rather a fluid experience, where one’s shelter circumstances and options may shift and change quite dramatically and with frequency.

Under this definition, a woman fleeing domestic violence by staying with friends, family or others in traditional housing, could be considered provisionally accommodated (also known as hidden homelessness) or at risk of homelessness – depending on the quality and security of the housing. Then there is the fact that many women who do leave abusive/violent do end up homeless, often with their children.

The relationship between domestic violence and homelessness

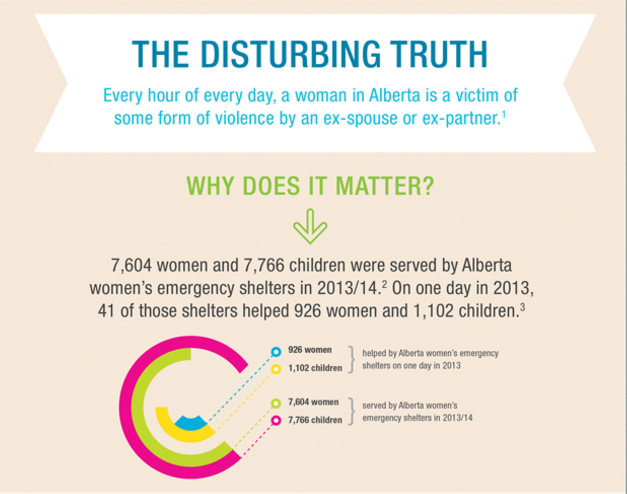

There’s a multitude of studies establishing the link between domestic violence and homelessness. According to the Rose Campaign, over 100,000 Canadian women and children turn to emergency shelters every year due to domestic violence. One 2009 report from the U.S. stated that 63% of women surveyed who were experiencing homelessness had experienced domestic violence. And while domestic violence is an important factor, there are always others involved. As these narratives from homeless women in Arizona illustrate, poverty, systemic issues and individual circumstances also play large roles in creating homelessness.

Many people judge women who don’t leave violent and/or abusive relationships and ignore the very real issues they will face if/when they do. Financial wellbeing is a huge concern, as single women and especially lone mothers are overrepresented in low-income brackets. As I wrote in another post: “A 2009 YWCA report discusses the fact that women are disproportionately represented in the low-income bracket. 70% of Canadian women work part-time and women make up two thirds of the workforce earning minimum wage.”

Income issues are even more complex for women who are new to Canada, who may not be legally allowed to work and whose partners may control their status. Guruge, Roche and Catallo (2012) highlight some situations that can affect immigrant women, including: psychological abuse, language barriers, misrepresentations of Canadian law, and post-traumatic stress from current abuse, the experience of living in war-torn areas and/or adjusting to life in Canada.

Women leaving abusive partners also often fear retaliation/additional violence, and the pain of losing one’s home. They must also navigate a lack of affordable childcare and housing, as well as a patchwork system of social services. In their research, Tutty et al. (2008) point out that many women who stay in violence against women (VAW) shelters do not find safe or secure housing afterward:

On exiting a …(VAW) shelter, women are often faced with inadequate housing and financial support that leave them with a choice between homelessness or returning to the abusive partner. While emergency and second-stage VAW shelters are essential services that can assist women to prevent them from becoming homeless, they are short-term solutions that are also constrained when assisting women to find safe and affordable housing in the community. Abused women and their children can slip through the cracks, sinking into a life of poverty, unsafe housing, or becoming homeless for extended periods.

Though women fleeing violence face much adversity, their strengths must also be celebrated. In her study on violence, women and homelessness in rural areas, Wickham draws attention to the importance of love in surviving abusive situations:

… I heard from mothers about the absolute love they have for their children and the determination to keep them from suffering. I heard from service providers who saw the determination manifested in the unbelievable strength women bring to their experiences. Strength was embedded in love for their families, their pets, their people, and their futures while being held up by maybe one friend, one supporter, or someone who was no longer alive. The reality is that love will keep a woman going for great periods of time and through many challenges that mainstream society would call unfathomable. However, society expects women to pick themselves back up again, time after time, while government systems fail and the root causes of violence remain unaddressed.

Moving forward, as always, it is clear we need to focus more on the systems failures that lead to poverty, violence and homelessness; and work towards integrated, preventative models. Part of taking a step in this direction is acknowledging that women fleeing violence are indeed homeless, and giving them the necessary support in finding safe and supportive housing.

For more resources on supporting women fleeing domestic violence, check out:

- “No cherries grow on our trees!” The Take Action Project

- Closing the Gap: Integrating Services for Survivors of Domestic Violence Experiencing Homelessness – A Toolkit for Transitional Housing Programs

- You Are Not Alone: A Toolkit for Aboriginal Women Escaping Domestic Violence

This post is part of our Friday "Ask the Hub" blog series. Have a homeless-related question you want answered? E-mail us at thehub@edu.yorku.ca and we will provide a research-based answer.

Photo credit: Alberta Government, full infographic here