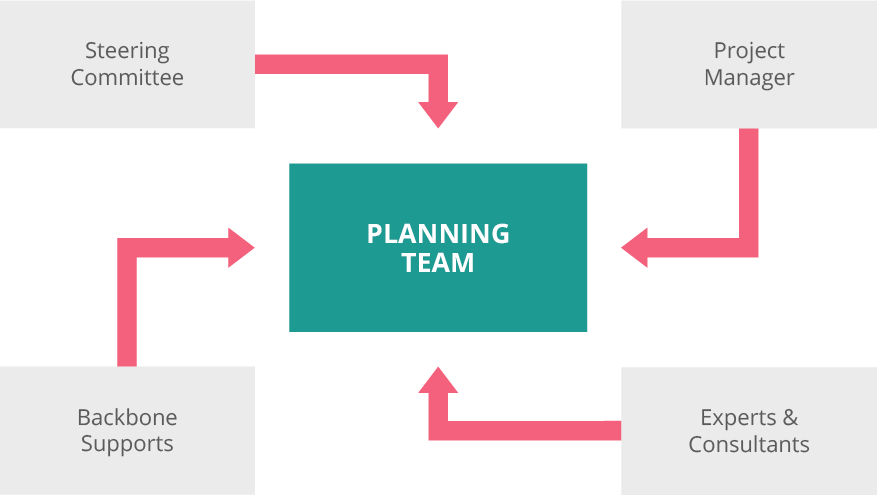

There are four main components of the planning team that you will want to consider: note, that you may have all of these roles or a combination thereof depending on local context and resources.

Figure 4: Planning Team

1. The backbone supports

An essential early decision in the plan development process involves the selection of the ‘backbone support’ organization. At times, this can be a straightforward matter as various groups or individuals may already play a convening role in your community on similar issues. Common backbone supports for youth plans include Community Entities, United Ways, local governments and service provider agencies.

Backbone supports play convening roles in the plan development process. While they may have a stake and opinions with respect to the ultimate plan direction, they are not making decisions unanimously; rather, they provide the infrastructure necessary to undertake the research, consultation and solution-generating work of the broader community. These organizations have the capacity to organize meetings, bring together stakeholders, undertake research and analysis and write the actual plan document.

Table 9: Backbone Supports Activities & Outcomes

| BACKBONE SUPPORT ACTIVITIES | SHORT-TERM OUTCOMES | INTERMEDIATE OUTCOMES |

|---|---|---|

| Guide vision and strategy | Stakeholders share a common understanding of youth homelessness and how to end it. | Stakeholders’ individual work is increasingly aligned with the common agenda outlined in the Youth Plan. |

| Support aligned activities | Stakeholders increasingly communicate and coordinate their activities toward common plan goals. | Stakeholders collaboratively develop new approaches to advance an end to youth homelessness. |

| Establish shared measurement practices | Stakeholders understand the value of sharing data. | Stakeholders increasingly use data to adapt and refine their strategies on an individual and collective basis. |

| Build public will | Community members are increasingly aware of youth homelessness. | More community members feel empowered to take action on the issue of youth homelessness. |

| Advance policy | Policymakers are more aware and supportive of the plan’s policy agenda. | Policy changes increasingly occur in line with the plan’s goals. |

| Mobilize funding | Funding is secured to support the plan’s goals. | Community and government funds are increasingly aligned with plan goals. |

It is critical that the group responsible for the backbone supports is respected, trusted and capable of delivering on these essential functions. It is always a good sign when diverse stakeholders approach a potential organization to take on this work versus the organization self-selecting without community support.

This was the case in Edmonton, where Homeward Trust was approached by diverse groups to take on the backbone organization role and deliver a local plan with the input of a steering committee. Communities where organizations assume this leadership role without broader stakeholder buy-in have found their ultimate success hampered by the decisions made in the early stages of the plan development process. There is a need to carefully balance the need for action and leadership in community while respecting diverse views. While this may be obvious, it is often not done in practice. Plan development is fraught with tension as stakeholders wrestle with pre-existing issues of contention and legitimate threats to the status quo related to determining a new vision and managing funding implications of the plan.

This is why the role of backbone supports is so essential. Lead staff often negotiate this tension in community, act as the ‘glue’ pulling people together at the same table and move the process forward, while respecting diverse viewpoints.

Backbone supports are not necessarily located in one particular agency, however; in some communities, several stakeholders come together to share accountabilities for these functions. In Wellington County, three organizations worked together to perform the functions of backbone supports and included both public and non-profit partners. In Calgary, the Calgary Homeless Foundation, City of Calgary (FCSS) and United Way provided funding for the human resources needed to develop a renewed youth plan, while service providers and funders shared the workload involved in setting up consultations and overseeing the workplan and budget for the process.

|

Common Characteristics of Effective Backbone Leadership

|

|---|

2. The steering committee

The group taking on backbone supports does not work on its own. The youth planning process is often led by a collaborative of stakeholders that come together to provide essential leadership for the plan. The committee’s role is to provide community leadership to advance the youth plan by overseeing the consultation process with key stakeholder groups, research and analysis, plan development and launch.

Ideally, committee members are leaders from government and non-profit sectors, including public systems, community funders, the private sector and community. Membership should consist of representatives of key funders and public systems essential to ending youth homelessness, such as child protection, social services, education, corrections, health, etc. Members should include both on- and off-reserve Indigenous leadership, government representatives, those with lived experience, researchers and community members at large. For rural and remote communities, you will need to balance the representation regionally.

Figure 5: Steering Committee Stakeholders

Below is a list of groups you should consider representation from. Try to keep the committee between 10–20 members with scheduled meetings monthly and on a need-to basis for the duration of the plan development process.Engaging the right people on the steering committee can help you access critical information for the plan development work, but also open doors to potential allies in government that can push the plan forward in implementation.

Engaging influential public servants, for instance, can help champion the plan internally. This can go a long way toward ensuring your efforts land on the right decision makers’ desks. Strong advocates from the private sector can similarly champion the plan publically and engage their respective networks to support plan activities during the early stages of development as well as into implementation. Such champions can help elevate the community’s understanding of youth homelessness and how to end it and can advance innovative solutions, policy and systems change in their respective circles of influence and with government.

Table 10: Key Stakeholder Member Sources

| SECTORS | POTENTIAL MEMBER SOURCES |

|---|---|

| Service Providers | Youth-serving agencies |

| Homeless-serving system agencies (adult and youth) | |

| Poverty alleviation/prevention services | |

| Public System Partners | Police service/RCMP |

| Public & Separate School Boards of Education | |

| Child, youth and family services authority | |

| Metis child and family services authority | |

| Health services (mental health, addictions, emergency/ambulatory care) | |

| Correctional services | |

| Young offender programs | |

| Youth/adult probation | |

| Poverty reduction initiatives | |

| On- and off-reserve Indigenous leadership & government | Local associations/formal groups working on youth, housing and homelessness issues |

| Neighbouring Nations | |

| Nations within regional scope of the youth plan | |

| Nations whose members migrate to the community developing plan | |

| Government of Canada | Indigenous Affairs & Northern Development |

| Economic and Social Development | |

| Canada Immigration & Citizenship | |

| Justice Canada | |

| Public Health Agency of Canada | |

| Provincial/Territorial Government | Child protection |

| Indigenous relations | |

| Education | |

| Health | |

| Human/social services | |

| Housing | |

| Homeless supports | |

| Justice | |

| Domestic violence | |

| Income assistance | |

| Persons with disabilities | |

| Employment | |

| Municipal/intergovernmental affairs | |

| Status of women | |

| Local/Regional Government | Community/neighbourhood services |

| Social housing corporation | |

| Income assistance/rent subsidies | |

| Community Funders | Lead organization on local plan to end homelessness |

| Community Entity (if different from above) | |

| Municipal government community services | |

| United Way | |

| Local community foundations | |

| Philanthropists with interest in youth | |

| Youth | Existing youth tables (Youth Advisory Committees, etc.) |

| Key populations: Indigenous, LGBTQ2S, immigrant, etc. | |

| Private Sector | Chamber of Commerce |

| Landlords | |

| Landlords Association | |

| Homebuilders Association | |

| Philanthropists with interest in youth | |

| Broader Community | Research community (university, college) |

| Faith community | |

| Influential community members at large |

Steering committee members should have key competencies which align with the previously identified collective impact principles, including:

- Commitment to ending youth homelessness: Passion and belief that youth homelessness can be ended and the resolve to making this a reality.

- Collaborative leader: Demonstrated personal and/or professional leadership in multi-stakeholder efforts by building consensus and drawing people into a process of change.

- Politically astute: Broad non-partisan understanding of political and social issues influencing the public policy environment.

- Social change agent: Desire to deepen understanding of complex social and economic issues that take complex solutions and willing to take action to address these within their sphere of influence.

- Strategic: Understands the lay of the land and can work within it to advance collective goals.

- Decision maker: Has the capacity, authority and willingness to make/influence decisions that advance an end to homelessness.

- Practical: Has the ability to manage the details and get things done, while effectively managing shifting circumstances and arising risks.

- Influential communicator: Able to share ideas and can serve as a bridge between the various communities and groups with an interest in the initiative.

- Knowledgeable: Has demonstrated knowledge of relevance to ending youth homelessness.

A note on recruitment

An individual may be an excellent champion, but unable to commit the time required to sit on the steering committee. You may therefore want to structure your steering committee into an overarching high-level group, with working committees that take on the bulk of the workload. The steering committee would have higher profile leaders meeting less frequently and providing general guidance, open doors to key decision-makers and maintain public visibility of the issue. Conversely, working committees take on key activities involved in plan development, such as research and consultations. This provides you with an opportunity to recruit members for your working group that provide additional technical expertise around policy, evaluation, youth voice, service provision, research, etc.

In this model, recruiting high profile champions will be essential. Your ability to secure commitment will be influenced by a number of factors:

- Approaching the right individuals with a passion for ending youth homelessness at the right time, being mindful of their time commitments;

- Providing a compelling vision for the work ahead and demonstrating the potential contribution of the individual to ending youth homelessness;

- Leveraging social networks to seek members using existing relationships – in many ways, it’s who you know and finding personal connections that can help you recruit the right champions will be more effective than a cold call; and

- Having a clear set of expectations laid out before you begin recruitment will be essential to help potential champions have a sense of the proposed workplan and expectations.

As is evident, someone has to oversee this recruitment process for the steering committee. It will likely fall to the backbone supports and dedicated project manager, with the assistance of other interested individuals on a more informal basis.

Put concerted efforts into recruiting a chair for the steering committee, who can then reach out to the larger pool of identified candidates for recruitment. This will require you to help identify target individuals early on and use a snowball technique to identify additional potential members as you go through the recruitment process.

Once the steering committee and working committees are established, Terms of Reference should be agreed upon. You may have already developed a draft used in the recruitment phase, but it is now up to the steering committee to finalize these.

The Terms of Reference for the steering committee essentially acts as the guiding document for the plan development process, as such they should have clearly delineated:

- Purpose and activities for the steering committee,

- Membership and core competencies,

- Roles and responsibilities for steering committee members, backbone supports, working committee and the project manager,

- Workplan and budget with clear timelines for plan development and launch,

- Meeting schedule,

- Guiding principles for the work of the committee, and

- Committee approach to decision-making process, attendance requirements, confidentiality and conflict of interest.

3. The project manager(s)

Without doubt, the role of the project manager is essential to the development of the youth plan. Ideally, your project manager is almost exclusively dedicated to supporting the plan development process for a set period of time, though this may not always be feasible. Acting as the quarterback for the duration of the process, the person charged with this role will have tremendous impact on the overall success of the effort.

Ideally, the project manager will have experience providing leadership at the community level and will understand local community processes and youth homelessness. They are effectively responsible for overseeing all aspects of the planning process and delivering the workplan activities. Their role can include:

- Ongoing liaising with the steering committee,

- Organizing community consultations,

- Completing key stakeholder interviews/ meetings,

- Providing project coordination support (note taking, meeting space, ongoing communication),

- Undertaking research and best practice analysis and

- Preparing briefing documents, reports and proposals.

The ideal candidate has experience in the non-profit environment and leadership experience with the ability to mentor, coach, engage and inspire colleagues and stakeholders. They have demonstrated capacity to negotiate with a variety of community stakeholders, excellent written and oral communications skills and interpersonal skills.

General competency requirements:

- Project Management Skills: Proven strong project management skills with ability to multi-task and set priorities within tight timelines.

- Anti-discrimination Orientation: Recognizes the need to be inclusive to women, LGBTQ2S, racialized minorities, Indigenous people, ethnocultural communities, etc.

- Credibility: Demonstrated ability to build organizational trust in his or her professionalism, expertise and ability to create solutions and deliver desired outcomes.

- Culturally Congruent: A passion for, belief in and communication of the vision, mission and guiding principles driving the plan to end youth homelessness. Will promote a transparent, ambitious, goal- and achievement-oriented culture. Demonstrates a strong work ethic and youth-centred approach.

- Building Effective Teams: Creates strong morale and spirit in her/his team; shares wins and successes; fosters open dialogue; delegates appropriately to team; defines success in terms of the whole team; creates a feeling of belonging in the team.

- Collaborative and Collegial: Works well with others, whether at the most senior levels, with direct reports or with others across the organization. Understands how to work with the community in a collaborative manner.

- Managing Change: Ability to adapt and thrive in a changing environment; capable of maintaining high levels of performance under pressure.

- Results Oriented: Sets high standards of performance including setting goals and priorities that maximize available resources to deliver results against the initiative direction, objectives and public expectations. Will monitor progress and make adjustments as necessary on an ongoing basis.

- Effective Facilitator: Can manage the feedback process, engage multiple stakeholders, identify and lead critical conversations and build consensus.

Project managers require a high level of support from their home organizations in cases where the youth plan is added onto their existing workload. This means, first and foremost, that they are provided with the time to deliver on the youth plan. Having someone add the youth plan to their workload without taking something off will create an unrealistic expectation and ultimately impact the quality of the plan.

Another option is to second a staff to the project for a limited period or to hire an external contract project manager to oversee the process. In cases where the project manager role is being divided amongst steering committee members, the expectations of each contributor should be made clear to ensure mutual accountability is maintained as members depend on one another to deliver key activities. The role of the project manager can also be divided among several positions within the backbone supports, leveraging technical skill-sets and managing workload demands more effectively.

4. Working with consultants & experts

As you contemplate resources, you will need to decide who will write various aspects of the plan. Communities often contract out part of their plan to consultants; while there are benefits to this approach, you should keep some considerations top of mind if you are moving in this direction.

There are definitely benefits to bringing in an external expert to help you with technical aspects of the plan such as cost modelling, which you may not have the on-hand capacity to undertake. Consultants can also lessen the time required of lead staff by taking on the research and consultation pieces or parts thereof. They can be important members of the planning team who work alongside lead staff and the steering committee.

However, consultants can also become barriers in the plan development process. First consider if you can do the work without external assistance. Ask yourself what benefits a consultant brings to the process. You have to do your homework to ensure you bring in the right person as well; someone who is divisive in community, has a history of missing timelines and/not delivering, etc. would obviously be a hindrance. Unfortunately, we don’t always realize we have the wrong consultant until problems emerge. It would best to put in place processes that ensure you are not in this position in the first place.

A Way Home and the COH are useful resources for identifying and selecting consultants you may want to leverage in this process as well.

Depending on what aspects you are looking to contract out, you’d look for a consultant with the following attributes:

- Recognized expertise in the issue of youth homelessness;

- Able and willing to support your team’s capacity building on technical issues;

- Respected and trusted by the diverse stakeholders involved in the plan;

- Excellent organizational, communication and interpersonal skills; and

- Track record of outstanding work, delivered on time and on budget.

In some instances, you may consider bringing in an external expert (paid or unpaid) to deliver key messages in your community – such as a keynote address during a community event to rally support for the plan. It can be useful to have a recognized, well-respected person in this role to kick-start the community’s thinking in a new direction. However, depending on how the message is delivered and received, the external expert can also be discordant and cause further tension in the community. The planning group will have to consider risks when moving in this direction very carefully. It may be wiser to bring the external expert in on a more informal basis to give you advice on your proposed direction and ‘look over your shoulder,’ pointing out potential pitfalls and promising directions you may be unaware of.

A kick-off event with key officials and the external expert can get the issue in front of the media from the beginning. You can leverage this event to get to know your media contacts, raise awareness about the initiative with them and begin their engagement in the process. Having a media presence throughout the planning and implementation process will help keep the issue top of mind within the broader community, ultimately enhancing its likelihood for support and impact.

Some considerations in hiring consultants:

- Does the plan team have capacity (expertise and time) to do the work without a consultant? This includes members of your steering committee who can take on pieces of the work.

- What workplan items can be assigned to a consultant?

- Do you have the resources to hire the right consultant?

- Does the plan team have the capacity to manage a consultant and support the necessary knowledge gathering the consultant might require?

- What items should not be done by a consultant? Are we missing out on building relationships ourselves by contracting out the community consultations?

- How can we leverage the consultant’s expertise to build our internal capacity to take on the technical aspects of the plan so we don’t rely on external experts on an ongoing basis?

- What are the drawbacks of relying on external expertise for this work?

If you hire a consultant, ensure an executed contract is in place that clearly outlines your respective roles and responsibilities in the project, their estimated scope of work, budget, timelines and deliverables.

At minimum, the contract should lay out:

- Project scope;

- Proposed approach;

- Detailed workplan (tasks, timelines and hours); and

- Itemized budget.

Ensure the contract includes a clause that enables you to use the knowledge generated by the consultant without their future permission. It is important for you to understand that the consultant owns the rights to the intellectual property they develop, even under contract with you, unless they explicitly allow your use of their product. It is advisable that you have ownership of the intellectual property developed; it would be recommended that you do not engage in agreements that do not ensure this.

An example of such a clause could read as follows:

Any copyrightable works, ideas, discoveries, inventions, patents, products or other information developed within this project will be the exclusive property of “Your Organization Name.”

Another example that may be useful is including a clause around Open Source in your contracts. This would ensure that a shared understanding of Open Source is built into contractual agreements with facilitators and consultants and understood at the local level. Sharing and documenting includes sharing of local models, templates, data collection tools and other resources with the A Way Home program staff and the participating communities as they are developed, including those developed by partners or contracted partners, consultants and facilitators.

Use your legal counsel in these matters to ensure your organization is fully protected. If you do not have a standard contract form, have your lawyers draft one for you.

When you do run into troubles, consider whether the relationship is salvageable and take steps to redress your concerns. If these are not remediated, move quickly and explore your options for terminating the contract.